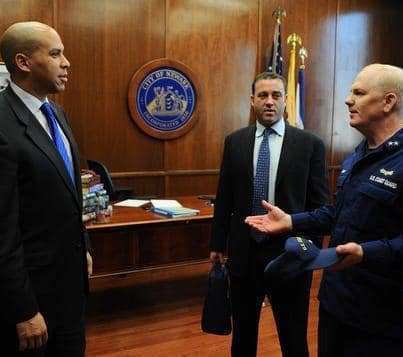

ABC News Tours Hillary, Bernie Campaigns’ Unionwear Shop

ABC Breaking News | Latest News Videos

ABC News takes a deep dive into Newark, NJ-based Unionwear, a union shop producing all those Hillary, Bernie, and Anti-Trump logo products.

TRANSCRIPT

Josh: What’s up guys? I’m sure you’ve seen this before. We all have. This hat is actually currently made in downtown Los Angeles, but ground zero for campaign merchandise here in Newark, New Jersey at Unionwear. It’s not just Donald Trump’s campaign who has hired advertising companies. It’s Hillary, it’s Bernie Sanders, it’s Jeb Bush, it’s Mick Huckabee. Take a look at this table guys. There is New Jersey’s own Chris Christie. So these campaigns, they hire advertising firms that then use this company, Unionwear, to make all of these hats. Even some candidates who are no longer in the race. There’s Jeb Bush for 2016. So we’re seeing a little bit of it all. There’s also handbags here. I want to take you back there. Another funny thing, this place has been involved since Al Gore run. Ever since 1992, they have been making merchandise like hats and bags for the conventions. These employees are all engaged as well. I want to bring in the president, Mitch Cahn. Mitch, hop on in right now, live on ABC Digital. Talk about how your business has been impacted by the 2016 election?

Mitch Cahn: We’ve had to make more hats than ever. There have been so many candidates this year. We probably made baseball hats for nearly every candidate in the race. We’ll be doing work for the conventions. We’ll be doing work for parties in all 50 states.

Josh: What is it about your business, Unionwear here in Newark that it is so appealing, connected to these presidential campaigns on both sides?

Mitch Cahn: Well, for one thing, every single product we make is made in the USA. Every product is also union made as unions are a very big voting bloc in the election. We’ve made a name for ourselves by making presidential merchandise over the last 25 years.

Josh: Why don’t you show us some of those hats? Want to bring that Hillary hat?

Mitch Cahn: Sure. Here is a Hillary hat that we’re making. We are also presently making hats for Bernie Sanders and making hats – we’ve made hats for Jeb Bush and Scott Walker and Chris Christie during this election cycle.

Josh: Got it. Ben and Amna, while I have Mitch here and we’re standing here in Unionwear, you guys have any questions for us before we take you on a little tour and show you how these hats are made and introduce you to some of the employees as well?

Ben: Yeah. It’s actually funny because when like a team loses the Super Bowl, I always wonder where their hats go because they all of sudden bring out the winner hats. Oh, you won the Super Bowl. It says winner. What is the most obscure hat that he has? Like is there a hat from like 15 years ago that a candidate ran, and he just keeps the hat because it’s got to be very cool nostalgia.

Josh: Yeah Mitch as we know, not every candidate is successful. You’ve been in the business for a while. What is the most rare hat that you have? Have you kept any of them as collectors items?

Mitch Cahn: I keep some fun ones. I have a Kucinich hat. I have hats from John Edwards. I have hats from Joe Lieberman. I’ve got a lot of hats from senate candidates as well that are in our showroom.

Josh: While Mitch is talking and definitely chiming in with another question, got to love this Scott Walker army hunting hat.

Amna: Oh, look at that.

Ben: Wow, that’s duck hunting right there.

Josh: I will not put it on for you guys.

Amna: Josh, why don’t you take us on a little tour of the facility? Let’s see where these things are made.

Josh: Definitely. Mitch, let’s do a little tour. Why don’t we start with the Drumpf hats and what’s being made at this station right here?

Mitch Cahn: Sure. We start over here where we cut fabric into little triangles. In this area right here, we take the triangles, we call them panels and we sew them together to make the crown of the baseball hat. You can see the back of a baseball cap right there. This will end up being a Trump parody hat. It’s kind of a parody hat of the ‘Make America Great Again’ hat. Once the fronts and the backs of the hats are completed, we take them over to our embroidery area.

Ben: Josh, when you have a moment, can you ask him who orders these Trump parody hats.

Mitch Cahn: This is where we take the front of the hat and we do this before the hat is made. We’ll sew down a logo on the hat. So Melba, tell us exactly what you’re doing at this stage?

Melba: We’re running a sample of the Bernie Sanders logo.

Josh: Do you mind if I hold that real quick?

Melba: Yeah, sure.

Josh: So guys, the pattern goes on this USB, which goes inside this machine. Melba here at the embroidery station, she makes those. Mitch, we had a follow-up question on those Trump hats. Actually funny story guys. I’m not sure if you’re fans of John Oliver’s show, but John Oliver is kind of the reason why those hats are doing so well. Tell us about those Make Donald Drumpf. Hats?

Ben: Make Donald Drumpf again.

Mitch Cahn: Yeah. John Oliver is selling a hat on hbo.com that says ‘Make Donald Drumpf again’, which is a parody of the ‘Make America Great again’ hat.

Josh: Drumpf is of course—

Mitch Cahn: The family name of Trump. Apparently, it’s an extremely popular baseball cap.

Josh: Tell us what popular means. How many have you sold? Why are you continuing having to make these hats?

Mitch Cahn: We are – well, HBO is selling the hat. We’re making all sorts of parody baseball caps here, including that hat. Maybe around 30,000-40,000 parody Trump hats just this month. Almost as much as some of the other candidates’ hats.

Josh: As we continue to tour, another kind of funny interesting thing. Of course, Unionwear, this is a union company, and many people would think that the Republican Party not always particularly fond of unions. They do make the hats made here, because this is a company that can get them out fast, and they specialize in this type of campaign gear. But for Republican candidates, they will not put the Unionwear label on the hats. So it will not say the word ‘union’ anywhere on those hats. For Democrats of course, they do say union made.

Mitch Cahn: I’m sure there’s one around here somewhere. We just got them out.

Ben: Josh, is any candidate off-limits or is it all fair game for the parody hats? Will he do any candidate?

Josh: Mitch, are any candidate off-limits or you will do any particular candidate or company that comes to you with business.

Mitch Cahn: Yeah, we will do work for all candidates unless it’s someone that I as the president/owner of the business completely disagree with their positions. I don’t want to help somebody get elected who I absolutely do not want to see be President of the United States.

Ben: Who is he voting for then?

Josh: So far, that has not happened in this campaign.

Mitch Cahn: No.

Ben: Ask him who he is voting for?

Josh: Do you mind telling us who you’re voting for?

Mitch Cahn: No, I’m not going to say who I’m voting for. But I appreciate all the candidates giving us work here and supporting domestic manufacturing. It’s very important.

Josh: While we still have you guys, why don’t we show them some of the handbags that you guys make. I know Ben has been in the market for, in particular, this Hillary handbag. I think you’ll like it, Ben.

Ben: Absolutely. I need this, a man bag — wow, this bag is huge. It’s got all kinds of secret compartments.

Josh: It is huge. Made in America right here in Newark, New Jersey.

Ben: I’d be worried to wear Make America Drumpf hat–

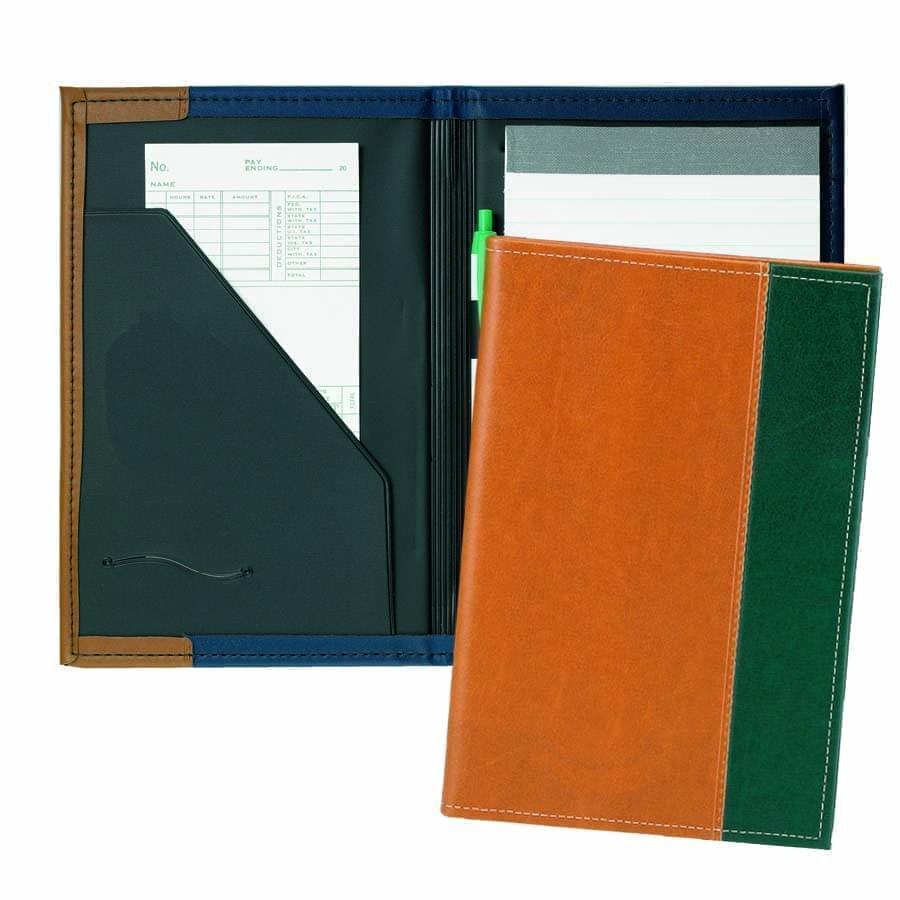

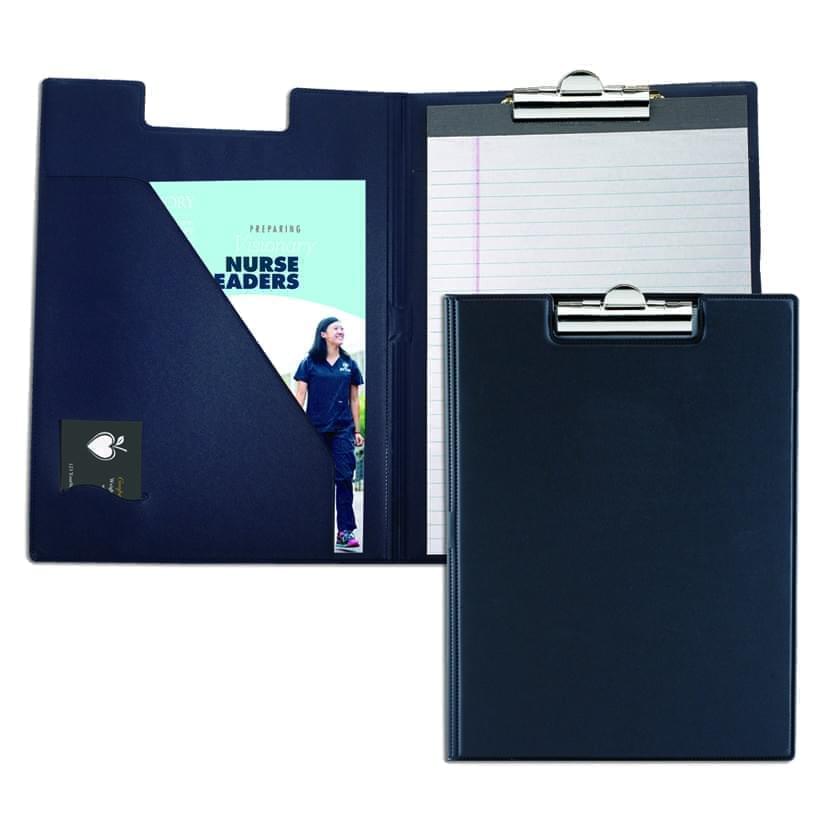

Mitch Cahn: We make tote bags, backpacks, garment bags, all sorts of luggage, handbags. Here’s some samples. Some of the tote bags we’re making for the Hillary Clinton campaign right here.

Josh: So Mitch, just walk us through the process. An advertising company reaches out to you and says we want a handbag or a tote bag to sell, wear and how – talk us through how that works.

Mitch Cahn: They usually come out here first and vet us to make sure that we are completely made in America, and we’re not going to embarrass them. Then they’ll send us designs. We’ll prototype the designs, sent it to them for approval. Then just start making the merchandise, it will end up on the website of the candidate. Probably end up in the convention centers and at official campaign events.

Amna: So I guess a question for Mitch is the merchandise any indication of how a candidate is doing. I notice he does both Hillary and Bernie hats. Does one outsell the other?

Josh: Mitch, a question from our anchor, Amna in New York. What’s doing better, the Bernie merchandise or the Hillary merchandise?

Mitch Cahn: It’s really hard to say. They are actually selling about equally.

Josh: What is equally? Can you give us any sort of ballpark?

Mitch Cahn: We will do several thousand dozen hats per month or so for each of the candidates.

Josh: Off of your question Amna, when a candidate’s campaign kind of starts to tank, of course, they’re going to put in less orders. So sometimes, this might be the first place here in Unionwear where they know. We in the media, we’re reporting on it, but they kind of know – they didn’t put in that order. Mitch, tell us about maybe a story from the past when that’s happened.

Mitch Cahn: I usually find out about a candidate leaving the race from the news, but it has been exciting. A few times I’ve known about the vice-presidential candidate before the convention. We had to sign confidentiality agreements. In a way that sports champions are crowned with baseball hats, they have merchandise ready for those vice presidential candidates.

Josh: Which candidate was that?

Mitch Cahn: I think that was when it was Lieberman.

Josh: Lieberman running with Al Gore. So talk about how that process went. Did the campaign call you and say –this is the design we want but do they have security here.

Mitch Cahn: Yeah, the ad agency. They didn’t have security here. They called at the last possible minute and said we’re going to need these for the convention. We’re going to tell you who it is at the last second. You have to sign this that you won’t tell anybody. I probably knew for about 15 seconds before the news already hit the internet.

Josh: So guys, when it comes to our Veep sweepstakes kind of guessing who the vice-presidential candidate is, now I know that my assignment will be living in a tent outside Unionwear in Newark, New Jersey waiting to see what orders they get.

Amna: I think that might be smart. Hey, one last question for Mitch, Josh. Can anyone place orders because I’m thinking if we want to try to get some hats made for maybe a Ben Aaron run in 2020.

Ben: Oh, you’re in trouble.

Amna: We may try to get those orders in now.

Ben: You don’t want to know my family name.

Josh: Yeah, Mitch, can you walk us through the process of – I know we’re not candidates. We’re not with the campaign, but can anyone order merchandise from you. How do they go about doing that? How does the visual of the logo and that come. Do they give it to you? How does that happen?

Mitch Cahn: Sure–we have tens of thousands of products on unionwear.com. You can select your products there and upload designs. Someone

will call you back with a price quote. It’s a relatively painless, quick process. During election season, it usually takes about three-four weeks for orders to be delivered.

Josh: Got to tell you guys, a lot of the rallies that I’ve been to, there are people outside those rallies especially Donald Trump rallies with tables of merchandise. That merchandise is actually made in China a lot of the times or overseas. They are, I guess you could say, counterfeit merchandise not made here, because the candidates made in America, such a big issue and important to them, they don’t want their gear made anywhere else. So if you see a table outside, most likely that’s not made in America. How will our viewers be able to find made in America campaign gear, Mitch?

Mitch Cahn: Usually just be going to the candidate’s websites. They all have web stores. The political parties also have web stores. Official web stores like demstore.com or gopshop.com where you can find the official merchandise.

Josh: Well, that’s the scene here in Unionwear at Unionwear, Newark, New Jersey. Back to you guys.

Mitch: Thanks.

Ben: Josh, thank you so much. We appreciate it. We’ll be expecting a strange random hat to be delivered at some point to this desk. We really appreciate it, man. I’ll be in big trouble. Make Colonomos great again. My real name is Colonomos.

Amna: Is that it?

Ben: It will be a bad thing. It wouldn’t even fit on the hat.

Amna: That’s going to take the whole width of the hat.

Ben: Yeah, it will go all the way around the hat.

Guess Whose Caps Are Outselling Donald Trump

At a nondescript factory near Branch Brook Park in Newark, workers have an easy way of gauging the popularity of any given presidential candidate.

As the only unionized American manufacturer of baseball caps, Unionwear has made logo-embroidered hats for candidates of all stripes.

If a candidate is doing well, his or her campaign might put in a large order for hats, said Mitch Cahn, president of Unionwear. Not so well? The campaign might cut back to putting in small orders on a week-by-week basis.

And just which hat has been popular? That would be “Drumpf,” the ancestral name of Donald Trump’s family, derisively parodied by British comedian John Oliver on HBO, which placed a large order for the hats.

“They put it on their website as a joke and sold way more than they expected,” Cahn said.

This small sector of Unionwear’s business has cropped up every four years since Al Gore’s campaign debuted candidate-themed apparel, Cahn said.

“There was really no way before the internet for these campaigns to sell their merchandise,” he said. “It’s not like they could have traveling stores everywhere they campaigned.”

That kind of campaign merchandizing raises money and turns voters into walking billboards – as well as building a connection with voters.

While the candidates differ on many things, they at some point have all ordered Unionwear hats, from Hillary Clinton to Ted Cruz to Trump, briefly.

And their detractors have ordered parody hats as well. Other Trump-related parody hats include “Make Donald Debate Again” and “Make America Gay Again,” Cahn said.

Unionwear stumbled into this customer category almost by default. Cahn had made a name for the business selling hats to high-end retailers like Nordstrom and The Gap. However, by the late 90s, almost all garment manufacturing had fled the United States for Asia.

The company held on until, lo and behold, they started to get orders simply because they were one of the few American, unionized manufacturers left standing after the brutal purge, Cahn said. Seeing which way the wind was blowing, they changed their name from New Jersey Headwear Corp. to Unionwear.

Anyone can order hats, whether it’s the official campaign, a political action committee, a union supporting a particular candidate, or state political parties.

Hence the hats Unionwear has made for the non-existent campaigns of Sen. Elizabeth Warren, Vice President Joe Biden, and Speaker of the House Paul Ryan.

Cahn said he’s noticed a difference between the orders for Democratic candidates versus Republican ones: The Democrats want to include the “union-made” label, while the Republicans prefer that be left off.

All, however, realize their campaign regalia must be made in America.

Early in the campaign cycle, Trump’s now-famous “Make America Great Again” baseball cap came under scrutiny when some said the item was made in China. It wasn’t; the cap in question was a knock-off sold online commercially, not by any official party or Trump-connected organization.

Trump used Unionwear for about a month last fall, then switched to a California factory, Cahn said. All told, they provided the campaign with more than 20,000 caps.

Although political attire isn’t a huge slice of Cahn’s business, the spotlight a presidential election puts on American manufacturing drives new business, he said.

“Every presidential campaign cycle there’s a news story that a candidate had an item that was made in Bangladesh,” Cahn said. “Then companies say to themselves, ‘Hey, We should probably look into getting something domestically.'”

Kathleen O’Brien may be reached at kobrien@njadvancemedia.com. Follow her on Twitter @OBrienLedger. Find NJ.com on Facebook.

NJ News12 Explains Why Most Campaign Hats Are Made in NJ

TRANSCRIPT

Reporter: And with all the political buzz generated during this election season, one local company is helping those presidential candidates make a statement, one baseball cap at a time. Nadia Ramdass explains.

Nadia Ramdass: Clinton, Cruz, Sanders and Trump; while these political heavyweights may differ on their political views, there’s one thing they all have in common. When they want Made-in-America gear, they turn to this factory in the Garden State.

Mitch Cahn: Anyone whose looking for hats made in America is coming here.

Nadia Ramdass: Unionwear tells us they are the only unionized American manufacturer of baseball caps. The Newark-based manufacturers’ companies include the military, progressive companies and political candidates. Unionwear has made promotional campaign hats, bags and other items for many Democratic and Republican presidential candidates for the last 16 years.

Mitch Cahn: By getting a product made in America, candidates sending a message that domestic manufacturing is important enough to their campaign that they’re going to make it an issue on their campaign.

Nadia Ramdass: The folks here at Unionwear can also gauge the degree of success for political candidate based on the volume of purchase orders over time.

Mitch Cahn: If somebody’s selling tens of thousands of baseball hats and somebody is selling no baseball hats, that would be a sign of one candidate’s being supported more than the other candidate most likely.

Nadia Ramdass: Cahn and his workforce expect to produce over one million hats by the end of the presidential election season; an opportunity he’s proud to have.

Mitch Cahn: I think it’s great that we are considered a symbol of made in America. Newark in particular is one of the strongest manufacturing cities in the country.

Nadia Ramdass: Nadia Ramdass News12, New Jersey.

Presidential Elections Heat Up USA Made Gear Manufacturers

With the presidential election season heating up, demand for candidate promotional products is growing by leaps and bounds. One supplier that knows a thing or two about the election rush is Unionwear, a custom apparel and accessories facility based in Newark, NJ, that offers made-in-the-USA items by employees represented by New York City-based Workers United, Local 155. The company has been producing election merchandise since 1996, when it designed a few hats for the Clinton-Gore campaign.

Four years later, in 2000, the Gore campaign gave away baseball caps from Unionwear to online donors, and the volume skyrocketed to more than 100,000 pieces. In 2008, the company made every hat for the Obama and McCain campaigns, as well as both conventions. This year, Unionwear is producing merchandise for seven campaigns, including Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump.

During the fall – even before the real election time kicked into high gear – the company was completing about 2,500 units a week for the major candidates, a number that the organization expects will triple by this summer. “Campaigns look for distributors who can handle everything from product development through fulfillment, including running the Web stores,” says Unionwear President Mitch Cahn. “Those distributors with experience in the political merchandise market have an advantage because they can project volumes and work on a week-to-week basis with their suppliers.

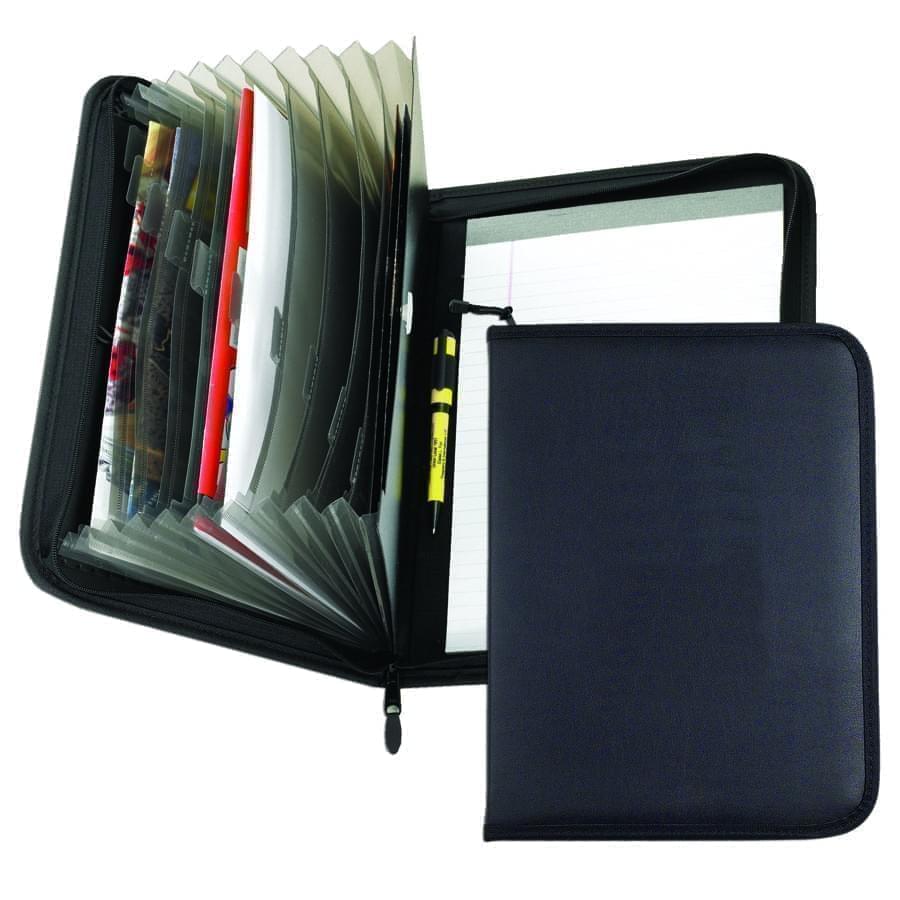

All campaigns vet their suppliers to make sure the goods are really made the way they’re labelled so merchandise doesn’t become a source of embarrassment.” In addition to headwear, Unionwear produces a number of different merchandise items, including all-over dye sublimation backpacks, tote bags and computer bags. They’ve even produced basketball jerseys and yarmulkes for Obama, what they called Obamakahs. “

There is a strong wave of USA made consumerism right now, but it shouldn’t be confused with patriotism,” says Cahn. ”While ‘American Pride’ sounds good, what actually causes buyers to connect with ‘USA-made’ are deep convictions about issues that support of domestic manufacturing can cure, including Worker Rights, Localism and the Maker Culture, which emphasizes the craft behind the product. Companies and campaigns are sensitive to being judged on their commitment to everything from helping rebuild our economy to the working conditions at vendors’ factories.”

Source: Counselor Magazine, Hail to the Chief Source: http://www.brandedgear.com/news/hail-to-the-chief/

Leader Bag’s Domestic Manufacturing Challenges

How did Leader Bag Co come to be?

Leader Bag Co was born from a love of beautiful design, and the desire to create a family-centered product that is truly missing from the marketplace.

When Meghan Nesher was pregnant with her son, Julien, she went shopping for a diaper bag that would work for both she and her husband. Coming up empty-handed, she opted for a Brooklyn Industries messenger bag; great for function, not so much for fashion. After a few months of use, she switched to the Fjällräven backpack; stylish and more comfortable, but not super functional. It was around this time that Meghan and her sister-in-law Liz Elliott, also a new mom, had their lightbulb moment: Why isn’t there a diaper bag that is beautifully crafted, simply designed and practical for both mom and dad?

Meghan, Liz and third sister-in-law Jess Nesher formed and funded Leader Bag Co as a family business in 2013. Since inception, we’ve enlisted the help of technical designer and manufacturing guru Jay O’Neill to bring our idea to life, and the uber-talented Lotta Nieminen to create our brand aesthetic.

Your brand is still only a year old, but what’s been the biggest challenge you’ve faced so far?

As a team of four, we all bring different strengths to the table, but at the same time, we all have strong opinions about pretty much every aspect of the business. We value playing to each other’s unique talents, but it’s not always easy with lots of cooks in the kitchen. We are constantly perfecting our team’s balance.

Manufacturing in the US – we were totally warned over and over that this was going to be difficult. All of us are perfectionists, and we’re all demanding, and I don’t think Unionwear knew we’d be so high-maintenance. Lucky for us, they have tons of pride in their work and are always striving to exceed expectations – which they did and continue to do.

Best thing you’ve learned?

Mistakes are opportunities, either to learn from or to create something new.

Your signature diaper backpack, the Julien, is a slick answer to a universal need; what kind of R&D did you pursue in the early stages?

Since we were all new moms, we did a lot of research for ourselves in the diaper bag market. We spent time looking at bags we didn’t like – even bought a few to compare. At the same time, we collected non-diaper bags we liked too, mostly based on modern aesthetics and strong craftsmanship.

We made lists of all the gear we stuffed into our baby bags and measured everything to make sure we designed the right size storage. We talked through where we would take the bag and what features we might need; for example, a hook to hang it in a bathroom stall while you change baby at a restaurant.

We collected tons of images on shared Pinterest boards – including inspiration for the brand, the bag and the lifestyle we wanted to promote.

Jay led us through multiple rounds of bag sketches – all different flavors and styles – until we settled on one we liked. He took the sketches to technical drawings, collected materials and had samples made. We went through at least three rounds of samples with Unionwear before we got our pack just right.

We put our samples on everyone’s backs, asked for feedback and took photos. We were careful to remove any design elements that seemed “girlie”, and made sure the shoulder straps were long enough to fit a really tall dad.

What features make the Julien awesome for carrying baby essentials?

The fact that it’s a backpack is key. We are all about leaving both hands free for tending to baby and being fully involved in family activities. Style-wise, the backpack is better for dad too – he’ll feel much more comfortable than if he were asked to carry a one-shoulder bag.

Ultimately, the Julien is awesome because of its storage and organization. We loved the idea of doing a drop-in “pouch” that can house some basics like a change mat, a few diapers, diaper cream and wipes. This way, you can just reach in and grab it for a quick change while you’re out.

We also made sure there were tons of compartments for all the essential gear. Outside, there are four decent-sized pockets for easy access, plus a clasp for hanging your keys. We also added stroller straps and hooks so you can easily hang it on your stroller when you don’t want to carry. Inside, there are four baby bottle (or water bottle) pockets, a sleeve for the change kit (or even a computer or iPad), a zipper pocket, and a few other larger pocket compartments. It’s wipe-clean and very utilitarian, but you wouldn’t necessarily know it from the outside.

When you’re running on no sleep and wearing the parental uniform of tracksuit pants and an old t-shirt, why is a luxe bag like the Julien important?

Being a parent isn’t always an elegant, effortless job. Especially when you’re a new parent running on empty and feeling overwhelmed.

The Julien immediately elevates your look: leather and canvas with rose gold details, all mixed with fine Made in the USA craftsmanship. And it’s effortless – it looks great with everything, is comfortable and keeps you organized so you can focus on what’s important: being present for your kid. There is absolutely nothing more chic.

Who else is making rad baby-related carry? Who inspires you to be better?

No one, in our opinion, is making a great diaper bag we’d want to carry! We do like Fawn and Cub’s change mat, and Ida Ising’s change mat/bag design.

Accessory and clothing companies outside of the diaper bag industry inspire us to be better, and companies that are producing their goods in the USA: Clare Vivier, Emerson Fry, Mansur Gavriel, Marine Layer, imogene + willie, etc.

What’s next for Leader?

There is a ton of room for us in the baby market right now. We see a lack of simple but beautiful and useful design, especially in kid accessories – which creates a whole lot of space for Leader to play.

What do you personally carry daily? And why?

Our Leader bags, of course!

Slate: What Do Bush and Clinton Have in Common? Unionwear

TRANSCRIPT: Bill Clinton, Al Gore, John Kerry, John McCain, Barak Obama, Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, and Jeb Bush all have something in common: the White House, yes, but also, this baseball cap factory in Newark, NJ, and more specifically, this guy:

“What they do is incredibly dexterous, I can’t do once what they do all day, which is take that thread and just throw it through a little hole.”

In 1992 at the age of 25 Mitch Cahn quit his job on Wall Street and bought a bankrupt hat factory in Jersey City at an auction sale. The idea was to make baseball hats for the fashion market including brands like the Gap. It was a trend at the time, but there was a hiccup. By 1994, American manufacturing was fleeing to cheaper manufacturing overseas and undercutting Mitch’s prices.

Mitch needed a new plan, so he turned to groups with vested interests in manufacturing goods in the US, and at the top of that list was political campaigns which is where this story gets interesting.

Cue James Carville: “Bush is buying up to $10 million in printing in Brazil. The president don’t buy American for his campaign.”

Making campaign gear offshore created the potential for a political scandal.

Cahn: “We are making hats for almost all the candidates, we are doing work for Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, Jeb Bush, If someone is having a hat made here, then they are making a decision to use American Labor.”

Campaigns aren’t the only clients who rely on Mitch’s US based factory.

There are socially complaint companies and non-profits who want to avoid any possible connotation that their products could be made in a sweat shop. The US Military. Promotional gear for labor unions and other companies looking to cobrand with the USA Made label. And the fashion industry.

But political campaigns are where Mitch has really dominated the market. Now located in Newark, his factory has been pumping out millions of hats from behind these doors, manufacturing for every Democratic primary candidate since 2000, as well as John McCain, George W. Bush, and Jeb Bush.

The bad optics of a made in China label aren’t the only thing driving political business to Mitch.

“The market is moving to small batch customization”, said Cahn. “Consumers are expecting to get products that they order in 2 or 3 weeks and you can’t wait 60 or 90 days for goods to come in on a ship. Your generally have to order a much larger quantity of goods when you bring things in from China, than you can domestically, and there is no way you can get things turned around a week or two.”

Which is key in the ever changing landscape of politics. Campaigns rarely have the luxury of folks ordering a set amount of products months in advance. They rely on quick turnarounds and flexible order sizes while replenishing their online stores. A bonus for the campaigns, especially those seeking much needed endorsement from a big union: Mitch also uses organized labor.

Once mostly the norm amongst textile manufacturers, Mitch’s pro union stance is a rarity these days, which is something he is proud of.

“Any difference in wages is made up of any increased productivity by our workers who are generally more content in their job. This was a union shop since the day we opened.

I believe over half of our people have been here for at least over 15 years.”

As manufacturing costs remain relatively flat in the US while rising dramatically in places like China, Mitch’s pro labor stance could become more prevalent. It is possible other manufacturers will follow Mitch’s lead and we’ll see more textile work come back to the USA. For now Mitch’s made in Newark factory is still producing the vast majority of the hats you see in the presidential campaign trail. But the most popular hat he has ever produced, you might have a guess if you have been tuned into the 2016 campaign season.

“Probably the hat we make the most here is the hat that says Make American Great Again which was made popular by Donald Trump and we are making that for the company selling the Made in USA version of that hat.”

Trump unsurprisingly uses a non union factory in California to produce the authentic version, but with all the polarization these days. It’s nice to know so many other politicians on both sides of the aisle can agree on thing. Newark is a great place to make hats.

ASI Radio: Election Year Bonanza for USA Made Products

This podcast can be heard on ASI Radio Strategy Sessions

Andy: Welcome to the Strategy Session Podcast, where ASI’s editors provide tips and tactics to help promotional product professionals improve their businesses. In every episode we go one-on-one with a business strategy expert to gather winning insights. The conversations are sure to be insightful and entertaining. This week on the strategy session podcast, I welcome David Bronson from Unionwear, which specializes in Made in the USA items. How are you today, David?

David: I’m doing well, sir, how are you?

Andy: Great. So, we’re going to talk about Made in the USA items and the increased interest in that. So, are you seeing more buyers looking to purchase items that are made domestically?

David: Oh yes, we have seen a surge, not just in interest but in actual orders. We’re helping dozens of new markets and industries co-brand with the most valuable brand in the world—Made in the USA. When we look at what’s driving sales, it’s not patriotism, it’s more strong convictions about issues that domestic manufacturing solves. Social compliance, for example. When someone buys an American-made product, he or she knows the workers who made the actual product are regulated by the same labor, safety and environmental regulations that the buyer benefits from. A lot of companies market their own products as Made in the USA, and they want premiums that are also Made in the USA so they send a consistent message.

Andy: So, as far as what’s driving the trend, you just talked about social compliance. Is that something that’s different today from maybe five years ago? Are people more interested in the issue of social compliance than they were before?

David: Yes. And it’s not just social compliance. We’re the only union cap company in the country, so they know that our workers have been vetted, if you will. The prices of imports have risen steadily by 20 to 25 percent for almost the past five years, while domestic pricing has remained flat. So while Made in the USA is not yet as competitive with imports, the premium paid for Made in the USA keeps decreasing. A lot more customers are willing to pay a premium for social compliance and consistent messaging.

Andy: What else is driving the trend? What other factors are leading the surge in Made in the USA orders?

David: Distributors ask me questions about the total cost of ownership. Importing products has a lot of hidden cost—there are high minimums, pre-payments, inventory, duties, taxes, shipping from overseas, sampling, travel, even in-factory inspections. We ask distributors to look at their client base to see if they have any clients that could appreciate co-branding with a Made in the USA label. We’ve seen a lot of renewed interest in baseball caps because of the Presidential campaigns—the baseball caps such as the ubiquitous “Make America Great Again” cap. And we all know who that is…

Andy: Right.

David: It’s a top item for political campaigns. Bags are popular, too, because they don’t require as much labor relative to materials as other products. But really, when you think about the hat, they can still wear that visibly in jacket weather. Candidates and supporters can wear that even though they’re wearing a suit at a rally or any kind of event, and it’s highly visible, because it’s on their head. We’re getting a lot of that increased business.

Andy: All right, how can distributors capitalize on this surge in interest in Made in the USA products?

David: I think distributors need to look at who they know or who they’re doing business with that might really care about Made in the USA. We keep hearing that there could be eight billion dollars spent on political campaigns over the next year. That’s the largest number that we’ve ever seen in this country. The battle is on, and it’s really been heating up, and for promotional items, they have to buy Made in the USA.

The traditional markets that we’ve had are Made in the USA for political or legal reasons. The Department of Defense buys these items for recruiting. Labor unions and government agencies…

Andy: Sure. Outside of government entities or political campaigns, what other buyers are most interested in items that are made in America? What markets should distributors try to target with these types of products?

David: The people that really are promoting themselves as Made in the USA or socially responsible include manufacturers like Lincoln, tech companies like Google, green companies like Whole Foods, non-profits like American Legion. We’ve grown what we call the small batch customization market the past year, where distributors want something turned around quickly, without large quantities or timing. Someone like Google has a need for it, and we have found a way to meet that need. They needed to be at a certain price, and we tweaked it a little bit.

One of the things at which we’re really strong is re-engineering products so that the Made in the USA label can work and be competitive. It’s our niche. It’s the one misconception that everyone has: “Oh, everything’s less expensive in China.” It doesn’t have to be. We can change a handle on a bag, take out a pocket or make it an inch different. We know how to make it work with our production department.

The distributors really get it, and they want something custom that is Made in the USA. We can say, what’s your budget? If they tell me they can spend $2500 for this giveaway or $40,000 for a bag that’s going to be at a place like Whole Foods, whatever it may be, we work backwards. We ask for the budget so we know what fabric to use; we know how much time it’s going to take, and we put that into the equation and come up with a costing, then share it with the distributor. Really, we’re an extension of their sales and marketing team, working with them from the ground up and building a product to hit their budget.

Andy: So what was Google looking for? Why were they so interested in purchasing Made in the USA items?

David: Google has a big push for it, which we love to see. A couple of the distributors that work with them, one in particular, just said they want to have as much made in the USA as they can for a program that they’re running. Sometimes people who want Made in the USA don’t always live up to billing on it, because they may get some sticker shock on some items.

Andy: Right.

David: But then we have certain items where we say, “Wait a second! If we’re within 5 to 15 percent of the cost, why wouldn’t you buy Made in the USA?” Think about the global impact, the carbon footprint when we’re making it here. We’re not shipping it from a port overseas, bringing it all the way over here and then cutting, embroidering, or finishing. Maybe the customer doesn’t have a Made in the USA or union requirement, but they just want something that’s totally custom. We’re doing dye-sublimation now, and we embroider flat panel; we can do things in embroidery so wide, so high, that a hoop can’t handle it. We’re growing with the times for those distributors that really care about something creative.

A lot of the people who care about Made in the USA like to say, “Wait a second, you actually do this here?” Yes, we’ve been here for 23 years. We’re right outside of Manhattan by about 12 miles. It’s pretty cool!

Andy: Very good. Let me bring the conversation back to price. You touched on it a little bit. Price does tend to be the big objection when it comes to purchasing Made in the USA items. So, I’m gathering that this isn’t the objection that it once was, but how should distributors overcome that objection if they’re still receiving it in the market?

David: It really is on a project-by-project basis. As I mentioned earlier, we re-engineer products to fit a budget so that Made in the USA can be competitive. There’s a misconception that, because wages are lower in China, the price is always lower. Imports actually have a much higher overhead than domestic goods. They have the inspections; suppliers have to deal with the language issues. We redesign a product so it’s much less labor-intensive than the same product coming from overseas. Eyelets on a hat, for instance… Adding them is time-intensive and increases the cost. Eliminate the eyelets, and you’ve saved 60 cents a hat. And if it’s a mesh-back hat, what are the eyelets needed for?

Goods made in China are usually designed with extra labor to save on materials. We do the opposite here. We want to save on labor and make it a better, leaner way. Our clients seem to be willing to spend just a little bit more for that Made in the USA label, especially when they see the quality of the product.

Andy: But ultimately you’re seeing the price differential coming together a little bit; the difference is not as stark as it once was?

David: Yes, it’s been about a 20 to 25 percent increase in the price of products being imported over the last five years, but domestic pricing has remained the same.

Andy: All right, I want to go back to the Presidential election a little bit. Obviously that’s big in the news right now and will be for the next year. Do you foresee that the impact of that marketing power trickling down to the local elections that will take place over the next year, as well?

David: That is one of the things that we’re revving up for, Andy, especially when we talk about the baseball caps. That’s where the marketing funds are being spent on this election. Candidates like Donald Trump have already shown in filing that they’ve spent more money on hats and shirts than on any other line items.

A number of candidates have been publicly called out for selling products that were imported. They’re self-correcting, and we’re seeing a lot of that increase. Some of our competitors aren’t making Made in the USA anymore because the costs have gone up. We’ve stayed the same, and when you look at the baseball cap as just one item, it is the ideal item, because sizing isn’t an issue, either. Wherever you go, you can wear it. It’s all about getting the candidate’s name out there and creating a bond between the wearer of the hat and the candidate. And what’s better than a hat? You’re not going to see a t-shirt if they have a jacket over it. That’s still a popular item, but we’re hitting winter now. The hat is like a walking billboard.

Andy: So, I’m guessing that you’re kind of doing back-flips every time that Donald Trump shows up in his hat, huh?

David: People say, “Why do you have this hat?” and “Why do you have that hat?” We try to explain to them that we’re a Made in the USA factory; we’re not taking any political stance. We’re a promotional product manufacturer, one of the few that actually makes something. We’re not just importing it and putting a logo on it. Whoever wants to buy these products, especially for a political campaign, and they need them to be made in USA, we’re open arms for.

Andy: There you go, David Bronson, the man who will make a hat for anybody.

David: Well, I don’t know if we’d say anybody yet… But in most cases, yes, we’ll do it.

Andy: All right, David. Thanks very much for joining me today on the strategy session podcast! We really appreciate your time.

David: Thank you very much for your time, and I hope to see you at the next show, Andy.

Andy: Sounds good, we’ll speak to you soon. This has been the latest episode of ASI’s Strategy Session podcast. To listen to all of our podcasts, go to www.asicentral.com/podcast.

PPB Factory Floor Tour: Unionwear’s USA Made Hats and Bags

Original article and photos of factory tour found at PPB Magazine.

Unionwear stitches pride into every U.S.-made, union-made cap and bag.

Twenty years ago, textile imports and overseas manufacturing were on the rise, as companies sought ways to do more business with less overhead. But at the same time, Unionwear/Konvex (UPIC: MADEINUS) was founded with a focus to keep manufacturing and production on American soil. Now the New Jersey company is a proud supplier of caps, bags and military goods that are both U.S.-made and union-made.

“We produce more than 600 different kinds of hats and bags in 360 color combinations,” says David Bronson, national accounts manager at Unionwear. “The most complicated bag we make is a casualty care bag for the U.S. Army, which requires 75 steps and over 100 pieces to produce. It is a fanny pack that holds medical supplies for Army medics.”

The simplest product, Bronson says, is a ski hat. To produce the popular cap style, machines knit yarn into a tube and employees cut the tube and sew it to shape. Unionwear customers’ top picks from the supplier are brushed cotton unstructured hats, structured cotton twill hats and tote bags.

To ensure a quality-finished product that’s wearable, usable and long-lasting, Unionwear has invested in dozens of pieces of specialized equipment—each dedicated to a single step in the process of assembling hats or bags. Additionally, Unionwear team members are experienced in the manufacture of such items. “We require employees to have five years of industrial sewing experience before they are allowed to finish products in our facility,” says Bronson.

“Our experience in making both hats and bags has benefitted the production of both products,” he adds. “In addition, we have become experts in decorating unfinished hat and bag parts, which enables us to get much better quality, larger embroidery fields and lower prices.”

Read on to see how Unionwear pieces together its popular line of hats.

The caps begin as a roll of fabric, which is drawn out and cut for the quantity needed per order.

Each panel of the cap is then die-cut according to the type of cap it will be—structured, unstructured and fitted are a few styles Unionwear makes.

At sub-assembly stations, the panels are sewn together and eyelets are sewn in as well. Embroidery is done at the flat-panel stage, as on this back panel.

More than 100 embroidery machines run daily at Unionwear

Visors are produced and attached to the crowns of each cap.

Next, the trimming, cleaning and quality-control process begins.

Finished products are inspected again before being polybagged, boxed and shipped.

ABOUT UNIONWEAR

Founding date

1992

Principal

Mitch Cahn

Number of orders filled per year

5,000

Number of employees

140

Size of production facility

70,000 square feet

140 sewing machine operators

Dedicated production lines

Baseball caps

Promotional tote bags

High-end tote bags

Military packs

Bucket and boonie hats

Patrol caps

Duffels, attachés, messenger bags and backpacks

Types of specialized equipment

Hat taping machine

Robotic blocking unit

Sweatband-making machine

Double-needle hat taping machine

Bucket-brim stitching machine

Hydraulic die-cutting clicker

Tajima embroidery machines

AS Technologies roll fuser

Zipper

Automated web-cutting machinery

Programmable tackers

Programmable box stitchers

Roll-to-roll zipper-to-gusset attach

Self handle machinery

Roll slitter for making handles

Make America Great Again Hat Brought To You By Lean Manufacturing

This podcast can be heard on Lean Blog

TRANSCRIPT: Mark Graban: Hi, this is Mark Graban. Welcome to Episode 234 of the podcast on November 16, 2015. Today’s guest is Mitch Cahn; he is president of Unionwear, a manufacturer of hats, bags and apparel in Newark, New Jersey. I first learned about Mitch and his company at the Northeast LEAN Conference recently, and I blogged about that. You can find a link to it at leanblog.org/234. Now, what caught my eye was the political hats they produce, including the famous red “Make America Great Again” hat that Donald Trump wears, among hats produced for other candidates. Beyond the surface of those hats is a fascinating story about competing instead of making excuses. As Mitch explains here in the podcast, Unionwear has been very successful, even though it’s producing in one of the highest-cost parts of the world. Unionwear has had to compete against imports from China and lower-wage southern states here in the US, and LEAN has been a major part of their strategy for improving productivity, reducing cost and being fast to market. Now, whether you work in healthcare or manufacturing, you’ll really love the story, the principles and the ideas behind Mitch, his company and his employees.

So, can you start off by introducing yourself and your company, Unionwear?

Mitch Cahn: Sure. My name is Mitch Cahn; I am the President of Unionwear. I started the business in 1992, and we’re based in Newark, New Jersey. We manufacture baseball caps and all sorts of headwear, and sewn bags, like backpacks, laptop bags, tote bags, garment bags, and messenger bags. Everything is 100% made in USA, and everything is made with union labor.

Mark Graban: What prompted you to start the business?

Mitch Cahn: I started the business in 1992. I bought a bankrupt baseball cap factory. Before that, I was working in investment banking, and I really didn’t like it. I wanted to be the client—I wanted to make stuff. So I spent about a year trying to come up with an idea to start a business, and then I came across this small baseball hat factory that had been foreclosed on in Jersey City, New Jersey, and I came up with enough money to buy the equipment at an auctions sale. I was going to do something different with that business—I was going to start selling baseball caps to the fashion industry, which was not a thing in 1992. You couldn’t go into The Gap or Macy’s and buy baseball caps back then, and I was actually successful very quickly. The idea caught on, and we picked up customers like Ralph Lauren, Nordstrom’s, and Izod, and we were helped by the growth of outlet stores at that time. However, by 1994, our entire business model collapsed because all of those clients started manufacturing in China. It happened really quickly; I didn’t see it coming. It was only a couple of years after Tiananmen Square; China became this giant in the market economy, and one of the first items they went after was baseball hats, because it’s almost all labor.

So we needed to come up with a new business model quickly, and around that time we came up with the idea of selling products specifically because they were made in the USA—going after the Made in USA market. We started with labor unions. We actually named the company Unionwear because unions were at that time one of our natural markets. We were the only union shop that made baseball hats. They were natural market for us, and then, by the year 2000, we expanded into political campaigns when the Internet made it possible for Al Gore’s campaign to raise money by giving a baseball hat away to every donor. We had that contract, and that’s been a big part of our business ever since.

We slowly looked into other markets that we found were buying American. After our LEAN transformation in 2007, we were competitive with non-union shops in the deep south. We could even compete with shops in Puerto Rico for military business—now that’s huge part of our business as well. In 2007, we bought a bag factory, and we did a LEAN transformation of that factory. Now that’s about half of our business. We’ve continued to expand our markets as the prices of imports continue to surge year after year, while our domestic pricing really remains flat. We’ve been able to break into more markets, particularly B2B markets that are looking at co-brands with the Made in USA label, which is really the most valuable brand in the world.

When someone gives a baseball hat or bag away, they don’t want that product to say “Made in China”. A lot of socially responsible companies give bags and hats away—Whole Foods, Google, and a lot of other companies—and they buy our products because the union label shows that the products were definitely not made in a sweatshop, and the Made in USA label shows that the products were not shipped halfway around the world. We’ve also been able to return to the fashion business over the last five years for the first time since the early 90s; we’ve been more competitive, and fashion businesses have been going for smaller batch manufacturing.

Mark Graban: It sounds like there’s a sense of purpose here, whereas a lot of industries and companies go with the flow. When business started going to China, all the lemmings said, “Hello, we have to go to China!” Even before you discovered LEAN, why was it important to you to stay in New Jersey?

Mitch Cahn: Well, I always reminded myself (and that’s the first ten years I was in business) that if I wanted to make money, it would have been a lot easier for me to stay on Wall Street. I didn’t want to make money; I wanted to make products. I find the manufacturing process extremely rewarding—I come into work, and someone meets me with an idea and leaves a sample. Then I have to figure out how to manufacture that sample, what machines to buy and what people to staff. To figure all that out and then go out in New York City and see people wearing and using the products is very rewarding. So, that was one part of it—I enjoy the maker experience. Second, from the outset I wanted to make sure that all of our employees were well compensated and had the same benefits as white-collar workers. Our union was the Ladies Textile Workers Union, and they said we were the first company (and we’re still probably the only company) that went to them before we started the business. We wanted to start a union shop because I knew we were going to give our employees the benefits that union workers would earn anyway. We might as well take advantage of the relationship that the unions had and use that for marketing purposes.

Mark Graban: I’m curious to hear more about LEAN. How did you first get introduced to the idea of LEAN?

Mitch Cahn: Around 2004, we faced with a lot of increasing expenses that were not really affecting the rest of the country. New Jersey was raising its minimum wage significantly ahead of the federal minimum wage. We were going to see our wages go up by about 30-40% pretty quickly. We also had big increases in health care at that time, and most of our competition was non-union shops in the South, and in right-to-work states. In most non-union shops, until ObamaCare, there was no health insurance offered, and we started to see the cost rise over a four-year period. We used to pay $50 a worker for health insurance, and by 2004, it was about $180. Then our real estate prices right outside the New York area started going up pretty quickly. So we couldn’t compete with the South, even for the Made in the USA work, and I was very concerned with our ability to remain a viable company. I started looking for a magic bullet, and I stumbled upon a LEAN 101 seminar that was being run by a New Jersey Manufacturers’ Extension Program (MEP). I took it, and it really blew my mind. For anyone who isn’t familiar with this program, it’s a national program, a one-day class that trains everyone from executives to factory workers on the whole LEAN process.

It puts people in a simulated factory making clocks. At the beginning of the day, everyone is using their own traditional methods to set up a production line and manufacture very simple clocks with the other executives—these are people who believe they know everything about manufacturing. At the beginning of the day, all these executives working together, with all their brainpower, might produce about 15 clocks an hour. Throughout the course of the day, LEAN principles are introduced one by one. Then they do another simulated flow, where the manufacturers take the principle they just learned and apply it to this mini-production line, and their volume increases. From the beginning to the end of the day, this group of executives will increase their production from 15 clocks to 300-400 clocks an hour! It really opened up my mind to the possibilities in my factory. I still remember when I came back, and all I could see was the opposite of LEAN. I was so angry! I was angry at everyone who worked for me for not seeing that they were doing non-value-added work all day, completely forgetting that I had just gone ten years without seeing any of that myself.

Mark Graban: Yeah, it becomes hard when you suddenly see waste and problems that you would have looked past before.

Mitch Cahn: I just wanted to do everything at once, and of course you can’t do that, but I did go back to MEP. I hired them for a small project while they submitted a grant proposal to the New Jersey Department of Labor to do a LEAN transformation for us. I brought in the consultant from NJ MEP, and he met with our plant manager at the time and me. The plant manager was very old-school, a traditional manufacturing production line person with about 30 years’ experience, and he was very skeptical of the consultant. All he wanted to know was how he was going to make our machine operators sew faster, and the consultant said, “I can’t do that. I don’t know anything about sewing, to be totally honest with you.” The plant manager asked, “How are you possibly going to improve our production here?” and the consultant said “Well, I’m only going to focus on what they’re doing when they’re not sewing. I worked in food companies, paint companies and car companies, and it’s always the same things. All I do is look for those things, and I train your workers and your management to eliminate those things through designing the factory differently and training people differently.” The plant manager was not convinced, but I brought the consultant in anyway, and we started with a really simple project. He went for the low-hanging fruit, and he took a look at our embroidery operation. We run about 12 embroidery machines here in the middle of our production process where we embroider our own hats and bags.

He spent a day observing that process and asked me, “How long do you think your machines are down between orders?” I remembered this from the spreadsheet that I looked at when I bought the machines, and I said about 20 minutes. He’d made a videotape, and he said, “Well, how about an average of about 2 1/2 hours?” I didn’t believe him. I watched the videotape, though, and I saw that the machines were indeed down as he’d said. In the past, I’d walked around and saw everyone working hard and running around, so I couldn’t understand why the machines were down for so long, and this was something that was going on 15 to 20 times a day—that was the average number of orders that we are pushing through the embroidery department a day. It turned out to a very simple problem with a very simple solution.

Our embroidery manager was a Chinese National who spoke English, and our embroidery operators were mostly from Spanish-speaking countries; they spoke a little English. The manager gave the instruction to go pick out threads of certain colors for an order. From the time she gave the instruction to the time they brought back the proper cones was about two and a half hours. Why? Based upon the instructions from the customer, she told the staff to look for, say, dark gray and dark green. The employees would go out to the shelves of closed white boxes with the thread color names on them, and the names were things like cement, and soup and canary and so on. They had to open box after box to find the right color thread. If they were lucky, it was the thread the embroidery manager had envisioned in her mind. If they weren’t lucky, they had to go back and return with another armful of threads. Then they would have to count out the threads—threads were shipped to us in boxes of 12, and our machines had 20 heads on them. So they’d count them out, they’d have to find the beginning of each cone and they’d have to bring them to the machine, put them on the machine and thread them, and then go back to get the next color. So the consultant’s first project was to get rid of all the color names and get rid of the boxes. We put everything in giant zip-lock bags. We color-coded our factory thread department like a rainbow, and we referred to everything by color number. We took all the threads and inventoried them in units of 20 to correspond to the machines’ 20 heads. Bags would come out to the table; the embroidery machines would be loaded. When it was over, cones would go back into the bags and be put back on the shelf. The whole process went from about two and half hours to 15 to 20 minutes pretty quickly, and we were easily able to see the power of LEAN in that department. We were sold.

So we went ahead, we got the grant, and we spent about two years putting in every facet of LEAN into the factory. We put in 5S, we put in all sorts of Kanban, we did single cell flow, and every one of these steps was really a phenomenal success for us. The 5S is something that we do every year, and it’s something the owner really needs to be involved in. For example, no one who works for me is going to throw a machine away. I’ll say, “Hey, we’re never going to use that machine! No one is going to pay for it, I just looked on eBay; we’re just going to sell it for scrap.” No one else will say that. So I need to actively show up, ready to get dirty for a couple of days.

Mark Graban: You mentioned the MEP programs, and for people who aren’t familiar with that, it’s a federally sponsored and funded program, but the MEPs operate at the state level. Some of the MEPs are doing work with healthcare organizations—the Ohio MEP, which works under the name TechSolve, is working with both manufacturers and healthcare providers. You talked about your healthcare costs going up. If you went into a hospital, I know you would see the parallels of why it takes so long between cases in the operating room. You talked about sewing—we’re not asking the surgeons to work faster, we’re just trying to maximize the amount of time during the day they can actually be surgeons, and that makes a huge difference in healthcare. Hopefully it’s going to help get costs under control. There are big parallels there.

Mitch Cahn: Yeah, there are a lot of parallels between healthcare and manufacturing, and coincidentally, while we were going through the first LEAN transformation my first son was born. The consultant, Dave Hollander, who shepherded us through this whole process, always tells how I came back from the hospital with all these ideas—it was Mt. Sinai in New York, which was already implementing LEAN—that I wanted to put in our factory. We still use a lot of those processes, like color-coded folders. There are so many LEAN improvements that we made, but one of the first principles that they taught us was to get rid of tables. Tables are evil! Unless you are using the table for a particular job, it’s going to be filled with garbage, on top and underneath, because that’s human nature. I noticed that in hospitals, if anybody needs a table, they get a rolling cart, so we gave everybody their own rolling cart. We designated places on the cart for everything that they need, and we gave them a small personal space on the bottom for their own stuff. We still use that, and apart from the productivity gain, the amount of space we gained was great.

Mark Graban: There is a good general LEAN principle: put everything on wheels! Be flexible so you can rearrange cells, rearrange the layout, make changes as customer demand changes to create different capacity—that’s definitely a great lesson. There was a letter that you had posted at the Northeast LEAN Conference. Could you talk a little bit more about the idea? I think a lot of manufacturers still don’t get the idea that they can’t create value by cutting labor costs. You have to redeploy labor in creating more value. Can you talk about what that’s meant for you and the company?

Mitch Cahn: Okay, we have a single-minded focus on creating value. Once the people who work here understand what that means, then it becomes a mindset, and it becomes very easy to implement any of the features of LEAN. We are here to create a finished product that needs to go right into a box and get shipped to a customer, and that customer will only pay for the value that we added to that product. So, if we’re making products, and we’re putting them in boxes, it’s inventory. We’re not creating value at that time; we’re just creating inventory. If we are creating work in process because people are working faster, that’s not finished product that we can sell. We’re not creating value. Now, if we are able to improve our productivity so that we’re creating a lot of value, and because of that I lay people off, I’m not actually creating value by doing that, either. Creating value means if I have a 100 people, and they used to make 1,000 hats a day, and now they can make 2,000 hats a day, and then 50 people can make 2,000 a day, I’m creating value by taking those other 50 people and creating another product with them. That to me is creating value. One of the keys to our success is our ability to measure the amount of value that we create. We have a process that we use. We do a lot of custom products—baseball caps are a very cookie-cutter process, that’s only about half of our business. The other half is bags, and every bag that we make is different. One day we’ll be making tote bags, the next day we’ll be making messenger bags. They’ve got totally different value street maps, and they’ve got totally different plant layouts.

So the first process for us is to figure out by doing a traditional time study, what is the cycle time of this product? What is the amount of time that the worker is actually adding value to the product, just picking two pieces of fabric and sewing them together? Or cutting that fabric—that’s really all we do that adds value. Everything else we do, such as looking for thread, waiting for instructions from a manager, redoing work or building up work in process, that’s not adding value. So if we take an attaché, and we know that attaché has 20 minutes of time that’s spent just adding value to that product, we can then measure our output in terms of minutes of work created against the amount of time that our workers worked. So we say, based on our time studies, our workers created 10,000 minutes of work today, but based on our time clock, they worked 20,000 minutes. That means they spent 50% of their time creating value. We measure this all the time. It enables us to get our pricing in check, enables us to know if we’re meeting our margins just by walking on the floor and seeing if there is work in process or if there are people moving around. It’s created goals for everybody to know whether the shop is LEAN and creating value or not.

Now, when we started this process, before we did any LEAN stuff, we were adding value only 20% to 25% of the time. The rest of it was all spent on non-value-added work. By the end of the process, we were adding value about 65% of the time, so our productivity almost tripled. It was difficult for most of our line workers to grasp the concept of what we were trying to sell to them, so we changed our measurement from percentage of time working efficiently (or adding value) to hours per day, and then people finally started to get it. We said, hey, you know, believe it or not, you’re only spending about two hours a day sewing, but you’re getting paid for eight. We’re asking you to spend about five and half to six hours sewing and get paid for eight, and they got it. That actually seemed like a great bargain to them. We were able to retrain everybody on LEAN principles; we made our own videos highlighting about 50 different non-value-added tasks that were regularly performed in the factories, so we could help people identify them.

Mark Graban: There are many things that are interesting and impressive about your story, but I think one of them is your involvement as an owner. LEAN is not just an operations strategy; it really is a key piece of your business strategy—it’s how you’re running the business and trying to be successful in the long term.

Mitch Cahn: Yeah, I think if I were to describe my job, I’m in charge of LEAN here. Everything else kind of takes care of itself, but LEAN is a battle against human nature, and it constantly needs improvement. If you’re doing LEAN properly, you need to continually improve, because if you are able to clear up one bottleneck, there’s going to be another bottleneck created somewhere else. You clear up that bottleneck in sales, and there’s going to be a bottleneck in production. You clear up that bottleneck, then you find a bottleneck in order processing. So I leave the top line growth up to the salespeople, and I take care of the growth and capacity by implementing LEAN principles throughout our entire organization.

Mark Graban: At the conference you displayed hats you’d produced for Jeb Bush and for Hillary Clinton, and there was the bright red, very familiar Donald Trump “Make America Great Again” hat. I was wondering if there were any stories, particularly behind the Trump hat. I’m curious about getting that business and trying to deliver a large number of hats relatively quickly. Are there any stories that you can share about that?

Mitch Cahn: As for Hillary Clinton’s campaign, we have been doing work for a company called Financial Innovations for decades. They’ve been managing the Democratic candidates for President for quite some time, ever since Bill Clinton. We have a very strong relationship with them. One of the reasons our company is regularly chosen to produce products for candidates is that we can produce goods quickly. Candidates don’t buy for the long-term—a lot of the primary candidates right now don’t know if they’re going to be around in two or three weeks, so they’re ordering every week. Instead of ordering 25,000 hats at a time, they’re ordering 2,000 or 3,000 hats a week. They need people who can turn things quickly, and because of our LEAN principles we can do that. We don’t have a lot of work in process on the floor, so we’re able to rush orders for people who need them. Another reason is that we’re a union shop, and the union label assures political campaigns that we’ve already been vetted for any sort of social compliance issues. That’s a smaller issue for the Republican side, though we have done a ton of Republican work. We did all of the work for the John McCain campaign, and we’re doing about four candidates right now. They just ask that we don’t put a union label inside the hat, for whatever reasons.

The second reason that we’re chosen is that we have a reputation. The candidates don’t want to get bitten by going to unknown manufacturer and finding out the products were actually made overseas. Our reputation as a military contractor says to them that we have been vetted by the military, and military goods need to be made domestically—not just all the labor but even all of the components for those products need to be sourced domestically. So I think that’s why they come to us. We never work with the campaigns directly; we always go through advertising agencies. The particular agency that we worked with on the Trump hat came to us from the Made in USA Foundation. They were concerned after they’d seen these hats being made overseas and contacted that agency, who told them that they don’t need to put “Make America Great Again” on a hat that says Made in China.

Mark Graban: Right. It’s interesting that of the three hats that were on display, the Trump hat was the only one that did not have Made in the USA embroidered on the brim. I think some people misunderstand LEAN as being about cost, when the primary thing is about improving flow, as you’ve described so well here—reducing setup times, improving productivity as a way of being more responsive to customers. Those are really powerful things, and they can lead to being cost-competitive, as it seems you’ve done at Unionwear.

Mitch Cahn: Yes, it has, and in many ways that you wouldn’t anticipate. LEAN has developed our dedication to measuring time and doing value stream maps for nearly every product that we manufacture. Our production process is data-driven. Over the last five years, much of our business has been re-shoring, where companies, usually in the fashion or promotional industry, have been getting products made overseas but are starting to reconsider. In the past, our hats might have been ten times as much as the hat made in China, but now they’re only 25% or 30% more. Companies are much more likely to switch now, so we’re constantly getting products that have been manufactured overseas, and we’re asked to quote on them for domestically made product. We look at the way these products are made overseas, perhaps in China, and it doesn’t make any sense to us. Take a tote bag for example—they throw labor at it to save on materials. It’s a dead giveaway when I see a tote bag that has a seam running along the bottom. If you cut that tote bag in two pieces, you’re going to get a lot more bags out of the roll of fabric than if you cut one big piece, but it adds a lot of labor and makes it a weaker bag. It makes no sense unless you’re trying to save on materials.

So we take these products and we reengineer them in a way that is LEAN and uses the least amount of labor possible. Between our productivity increases and our ability to reduce the amount of labor that goes into the product, we’re able to compete on many items, particularly in the fashion business.

Mark Graban: I really appreciate you being able to share your story both at the Northeast LEAN Conference and for taking time to talk with me here today, Mitch. Again, my guest has been Mitch Cahn, President of the company, Unionwear. Mitch, I was wondering if you want to talk about the company’s website, or ways people can learn more about your business, or if you have any final thoughts for the listeners.

Mitch Cahn: Sure, our website is unionwear.com. We have over 40,000 Made in USA products that you can search for and order directly on the website. You can contact me through the website if you have any questions about LEAN. I love helping other manufacturers who are just getting started in the LEAN process. I just want to warn you—it’s never a good time to start, but once you start, you will be rewarded. You’ll never finish, but you will be continuously improving.

Mark Graban: Well said, and thank you, Mitch, for that final thought and for being a guest here today on the podcast, I really appreciate it.

Mitch Cahn: You’re welcome. Thanks.

Introducer: Thanks for listening. This has been the LEAN Blog podcast for LEAN news and commentary updated daily is at www.leanblog.org. If you have any questions or comments about this podcast, email Mark, at leanpodcast@gmail.com.

Alternet: Buying America-Many Ways To Express Values with your Wallet

Buying America: The Many Astounding Ways You Can Express Your Values with Your Pocket Book

Shopping can be an ethical act.

By David Morris / AlterNet July 27, 2015

“Every person ought to have the awareness that purchasing is always a moral – and not simply an economic – act,” Pope Francis announced early this year. How can we spend our money as if our values matter?

In some sectors and for some values this is fairly easy. Food is an obvious example. Those who want to protect the environment and human and animal health will find abundant labels guiding them to the appropriate product: USDA Organic, free range, hormone free, grass fed. For those who want to strengthen community, shrink the distance between producer and consumer and support family farmers a growing number of grocery stores label locally grown or raised.

For those who want to support farmworkers as well as farmers, however, little guidance is available. The recently launched Equitable Food Initiative and Food Justice Certified labels hope to fill this gap. The former identifies food that has been harvested by workers paid a fair wage and laboring under safe and fair conditions. The latter offers three tiers of certification covering farm, processor and vendor/retailer. Only farms have been certified.

As for grocery stores, we can easily identify those cooperatively or locally owned. Going one step further along the supply chain we can use the Restaurant Opportunities Center United (ROC)’s Diners Guide to Ethical Eating downloadable app to identify restaurants that treat their workers well. Extra credit is given to non-chain businesses. To earn a favorable rating the restaurant must pay its non-tipped workers at least $10 an hour and tipped staff at least $7 an hour, grant all employees paid sick days and enable internal promotion.

The ethical consumer who wants to patronize a locally owned retail store in general can visit Independent We Stand and download its mobile app. Or go to AMIBA and BALLE to find a list of independent business alliances in over 100 cities many of which have hundreds and even thousands of individual member businesses.

There are few guides to locally and rooted manufacturers. But 3-year-old San Francisco Made offers an excellent model, interconnecting and nurturing its 325 member manufacturers located in that city.

The vast majority of products we purchase will come from regional and national firms. One can easily check to see if the company is American and sometimes that will be necessary even when we think we know from the product’s name what nationality the company is. As Roger Simmermaker, author of How Americans Can Buy American and My Country ‘Tis of Thee points out, “Swiss Miss is American (based in Menomonie, Wisconsin) and Carnation is owned by the Swiss.”

For those who want to go beyond where a company is headquartered to who owns it, a list of companies owned by their employees is available from the National Center for Employee Ownership.

Finding American made products as opposed to American corporations requires more legwork. Almost 8 in 10 American consumers say they prefer to buy American made products according to Consumer Reports. (Another survey found that for Americans ages 18-34 the percentage drops to 4 in 10.) Patriotic buying has gained considerable cache in the last few years and is beginning to change corporate behavior.