This podcast can be heard on Lean Blog

TRANSCRIPT: Mark Graban: Hi, this is Mark Graban. Welcome to Episode 234 of the podcast on November 16, 2015. Today’s guest is Mitch Cahn; he is president of Unionwear, a manufacturer of hats, bags and apparel in Newark, New Jersey. I first learned about Mitch and his company at the Northeast LEAN Conference recently, and I blogged about that. You can find a link to it at leanblog.org/234. Now, what caught my eye was the political hats they produce, including the famous red “Make America Great Again” hat that Donald Trump wears, among hats produced for other candidates. Beyond the surface of those hats is a fascinating story about competing instead of making excuses. As Mitch explains here in the podcast, Unionwear has been very successful, even though it’s producing in one of the highest-cost parts of the world. Unionwear has had to compete against imports from China and lower-wage southern states here in the US, and LEAN has been a major part of their strategy for improving productivity, reducing cost and being fast to market. Now, whether you work in healthcare or manufacturing, you’ll really love the story, the principles and the ideas behind Mitch, his company and his employees.

So, can you start off by introducing yourself and your company, Unionwear?

Mitch Cahn: Sure. My name is Mitch Cahn; I am the President of Unionwear. I started the business in 1992, and we’re based in Newark, New Jersey. We manufacture baseball caps and all sorts of headwear, and sewn bags, like backpacks, laptop bags, tote bags, garment bags, and messenger bags. Everything is 100% made in USA, and everything is made with union labor.

Mark Graban: What prompted you to start the business?

Mitch Cahn: I started the business in 1992. I bought a bankrupt baseball cap factory. Before that, I was working in investment banking, and I really didn’t like it. I wanted to be the client—I wanted to make stuff. So I spent about a year trying to come up with an idea to start a business, and then I came across this small baseball hat factory that had been foreclosed on in Jersey City, New Jersey, and I came up with enough money to buy the equipment at an auctions sale. I was going to do something different with that business—I was going to start selling baseball caps to the fashion industry, which was not a thing in 1992. You couldn’t go into The Gap or Macy’s and buy baseball caps back then, and I was actually successful very quickly. The idea caught on, and we picked up customers like Ralph Lauren, Nordstrom’s, and Izod, and we were helped by the growth of outlet stores at that time. However, by 1994, our entire business model collapsed because all of those clients started manufacturing in China. It happened really quickly; I didn’t see it coming. It was only a couple of years after Tiananmen Square; China became this giant in the market economy, and one of the first items they went after was baseball hats, because it’s almost all labor.

So we needed to come up with a new business model quickly, and around that time we came up with the idea of selling products specifically because they were made in the USA—going after the Made in USA market. We started with labor unions. We actually named the company Unionwear because unions were at that time one of our natural markets. We were the only union shop that made baseball hats. They were natural market for us, and then, by the year 2000, we expanded into political campaigns when the Internet made it possible for Al Gore’s campaign to raise money by giving a baseball hat away to every donor. We had that contract, and that’s been a big part of our business ever since.

We slowly looked into other markets that we found were buying American. After our LEAN transformation in 2007, we were competitive with non-union shops in the deep south. We could even compete with shops in Puerto Rico for military business—now that’s huge part of our business as well. In 2007, we bought a bag factory, and we did a LEAN transformation of that factory. Now that’s about half of our business. We’ve continued to expand our markets as the prices of imports continue to surge year after year, while our domestic pricing really remains flat. We’ve been able to break into more markets, particularly B2B markets that are looking at co-brands with the Made in USA label, which is really the most valuable brand in the world.

When someone gives a baseball hat or bag away, they don’t want that product to say “Made in China”. A lot of socially responsible companies give bags and hats away—Whole Foods, Google, and a lot of other companies—and they buy our products because the union label shows that the products were definitely not made in a sweatshop, and the Made in USA label shows that the products were not shipped halfway around the world. We’ve also been able to return to the fashion business over the last five years for the first time since the early 90s; we’ve been more competitive, and fashion businesses have been going for smaller batch manufacturing.

Mark Graban: It sounds like there’s a sense of purpose here, whereas a lot of industries and companies go with the flow. When business started going to China, all the lemmings said, “Hello, we have to go to China!” Even before you discovered LEAN, why was it important to you to stay in New Jersey?

Mitch Cahn: Well, I always reminded myself (and that’s the first ten years I was in business) that if I wanted to make money, it would have been a lot easier for me to stay on Wall Street. I didn’t want to make money; I wanted to make products. I find the manufacturing process extremely rewarding—I come into work, and someone meets me with an idea and leaves a sample. Then I have to figure out how to manufacture that sample, what machines to buy and what people to staff. To figure all that out and then go out in New York City and see people wearing and using the products is very rewarding. So, that was one part of it—I enjoy the maker experience. Second, from the outset I wanted to make sure that all of our employees were well compensated and had the same benefits as white-collar workers. Our union was the Ladies Textile Workers Union, and they said we were the first company (and we’re still probably the only company) that went to them before we started the business. We wanted to start a union shop because I knew we were going to give our employees the benefits that union workers would earn anyway. We might as well take advantage of the relationship that the unions had and use that for marketing purposes.

Mark Graban: I’m curious to hear more about LEAN. How did you first get introduced to the idea of LEAN?

Mitch Cahn: Around 2004, we faced with a lot of increasing expenses that were not really affecting the rest of the country. New Jersey was raising its minimum wage significantly ahead of the federal minimum wage. We were going to see our wages go up by about 30-40% pretty quickly. We also had big increases in health care at that time, and most of our competition was non-union shops in the South, and in right-to-work states. In most non-union shops, until ObamaCare, there was no health insurance offered, and we started to see the cost rise over a four-year period. We used to pay $50 a worker for health insurance, and by 2004, it was about $180. Then our real estate prices right outside the New York area started going up pretty quickly. So we couldn’t compete with the South, even for the Made in the USA work, and I was very concerned with our ability to remain a viable company. I started looking for a magic bullet, and I stumbled upon a LEAN 101 seminar that was being run by a New Jersey Manufacturers’ Extension Program (MEP). I took it, and it really blew my mind. For anyone who isn’t familiar with this program, it’s a national program, a one-day class that trains everyone from executives to factory workers on the whole LEAN process.

It puts people in a simulated factory making clocks. At the beginning of the day, everyone is using their own traditional methods to set up a production line and manufacture very simple clocks with the other executives—these are people who believe they know everything about manufacturing. At the beginning of the day, all these executives working together, with all their brainpower, might produce about 15 clocks an hour. Throughout the course of the day, LEAN principles are introduced one by one. Then they do another simulated flow, where the manufacturers take the principle they just learned and apply it to this mini-production line, and their volume increases. From the beginning to the end of the day, this group of executives will increase their production from 15 clocks to 300-400 clocks an hour! It really opened up my mind to the possibilities in my factory. I still remember when I came back, and all I could see was the opposite of LEAN. I was so angry! I was angry at everyone who worked for me for not seeing that they were doing non-value-added work all day, completely forgetting that I had just gone ten years without seeing any of that myself.

Mark Graban: Yeah, it becomes hard when you suddenly see waste and problems that you would have looked past before.

Mitch Cahn: I just wanted to do everything at once, and of course you can’t do that, but I did go back to MEP. I hired them for a small project while they submitted a grant proposal to the New Jersey Department of Labor to do a LEAN transformation for us. I brought in the consultant from NJ MEP, and he met with our plant manager at the time and me. The plant manager was very old-school, a traditional manufacturing production line person with about 30 years’ experience, and he was very skeptical of the consultant. All he wanted to know was how he was going to make our machine operators sew faster, and the consultant said, “I can’t do that. I don’t know anything about sewing, to be totally honest with you.” The plant manager asked, “How are you possibly going to improve our production here?” and the consultant said “Well, I’m only going to focus on what they’re doing when they’re not sewing. I worked in food companies, paint companies and car companies, and it’s always the same things. All I do is look for those things, and I train your workers and your management to eliminate those things through designing the factory differently and training people differently.” The plant manager was not convinced, but I brought the consultant in anyway, and we started with a really simple project. He went for the low-hanging fruit, and he took a look at our embroidery operation. We run about 12 embroidery machines here in the middle of our production process where we embroider our own hats and bags.

He spent a day observing that process and asked me, “How long do you think your machines are down between orders?” I remembered this from the spreadsheet that I looked at when I bought the machines, and I said about 20 minutes. He’d made a videotape, and he said, “Well, how about an average of about 2 1/2 hours?” I didn’t believe him. I watched the videotape, though, and I saw that the machines were indeed down as he’d said. In the past, I’d walked around and saw everyone working hard and running around, so I couldn’t understand why the machines were down for so long, and this was something that was going on 15 to 20 times a day—that was the average number of orders that we are pushing through the embroidery department a day. It turned out to a very simple problem with a very simple solution.

Our embroidery manager was a Chinese National who spoke English, and our embroidery operators were mostly from Spanish-speaking countries; they spoke a little English. The manager gave the instruction to go pick out threads of certain colors for an order. From the time she gave the instruction to the time they brought back the proper cones was about two and a half hours. Why? Based upon the instructions from the customer, she told the staff to look for, say, dark gray and dark green. The employees would go out to the shelves of closed white boxes with the thread color names on them, and the names were things like cement, and soup and canary and so on. They had to open box after box to find the right color thread. If they were lucky, it was the thread the embroidery manager had envisioned in her mind. If they weren’t lucky, they had to go back and return with another armful of threads. Then they would have to count out the threads—threads were shipped to us in boxes of 12, and our machines had 20 heads on them. So they’d count them out, they’d have to find the beginning of each cone and they’d have to bring them to the machine, put them on the machine and thread them, and then go back to get the next color. So the consultant’s first project was to get rid of all the color names and get rid of the boxes. We put everything in giant zip-lock bags. We color-coded our factory thread department like a rainbow, and we referred to everything by color number. We took all the threads and inventoried them in units of 20 to correspond to the machines’ 20 heads. Bags would come out to the table; the embroidery machines would be loaded. When it was over, cones would go back into the bags and be put back on the shelf. The whole process went from about two and half hours to 15 to 20 minutes pretty quickly, and we were easily able to see the power of LEAN in that department. We were sold.

So we went ahead, we got the grant, and we spent about two years putting in every facet of LEAN into the factory. We put in 5S, we put in all sorts of Kanban, we did single cell flow, and every one of these steps was really a phenomenal success for us. The 5S is something that we do every year, and it’s something the owner really needs to be involved in. For example, no one who works for me is going to throw a machine away. I’ll say, “Hey, we’re never going to use that machine! No one is going to pay for it, I just looked on eBay; we’re just going to sell it for scrap.” No one else will say that. So I need to actively show up, ready to get dirty for a couple of days.

Mark Graban: You mentioned the MEP programs, and for people who aren’t familiar with that, it’s a federally sponsored and funded program, but the MEPs operate at the state level. Some of the MEPs are doing work with healthcare organizations—the Ohio MEP, which works under the name TechSolve, is working with both manufacturers and healthcare providers. You talked about your healthcare costs going up. If you went into a hospital, I know you would see the parallels of why it takes so long between cases in the operating room. You talked about sewing—we’re not asking the surgeons to work faster, we’re just trying to maximize the amount of time during the day they can actually be surgeons, and that makes a huge difference in healthcare. Hopefully it’s going to help get costs under control. There are big parallels there.

Mitch Cahn: Yeah, there are a lot of parallels between healthcare and manufacturing, and coincidentally, while we were going through the first LEAN transformation my first son was born. The consultant, Dave Hollander, who shepherded us through this whole process, always tells how I came back from the hospital with all these ideas—it was Mt. Sinai in New York, which was already implementing LEAN—that I wanted to put in our factory. We still use a lot of those processes, like color-coded folders. There are so many LEAN improvements that we made, but one of the first principles that they taught us was to get rid of tables. Tables are evil! Unless you are using the table for a particular job, it’s going to be filled with garbage, on top and underneath, because that’s human nature. I noticed that in hospitals, if anybody needs a table, they get a rolling cart, so we gave everybody their own rolling cart. We designated places on the cart for everything that they need, and we gave them a small personal space on the bottom for their own stuff. We still use that, and apart from the productivity gain, the amount of space we gained was great.

Mark Graban: There is a good general LEAN principle: put everything on wheels! Be flexible so you can rearrange cells, rearrange the layout, make changes as customer demand changes to create different capacity—that’s definitely a great lesson. There was a letter that you had posted at the Northeast LEAN Conference. Could you talk a little bit more about the idea? I think a lot of manufacturers still don’t get the idea that they can’t create value by cutting labor costs. You have to redeploy labor in creating more value. Can you talk about what that’s meant for you and the company?

Mitch Cahn: Okay, we have a single-minded focus on creating value. Once the people who work here understand what that means, then it becomes a mindset, and it becomes very easy to implement any of the features of LEAN. We are here to create a finished product that needs to go right into a box and get shipped to a customer, and that customer will only pay for the value that we added to that product. So, if we’re making products, and we’re putting them in boxes, it’s inventory. We’re not creating value at that time; we’re just creating inventory. If we are creating work in process because people are working faster, that’s not finished product that we can sell. We’re not creating value. Now, if we are able to improve our productivity so that we’re creating a lot of value, and because of that I lay people off, I’m not actually creating value by doing that, either. Creating value means if I have a 100 people, and they used to make 1,000 hats a day, and now they can make 2,000 hats a day, and then 50 people can make 2,000 a day, I’m creating value by taking those other 50 people and creating another product with them. That to me is creating value. One of the keys to our success is our ability to measure the amount of value that we create. We have a process that we use. We do a lot of custom products—baseball caps are a very cookie-cutter process, that’s only about half of our business. The other half is bags, and every bag that we make is different. One day we’ll be making tote bags, the next day we’ll be making messenger bags. They’ve got totally different value street maps, and they’ve got totally different plant layouts.

So the first process for us is to figure out by doing a traditional time study, what is the cycle time of this product? What is the amount of time that the worker is actually adding value to the product, just picking two pieces of fabric and sewing them together? Or cutting that fabric—that’s really all we do that adds value. Everything else we do, such as looking for thread, waiting for instructions from a manager, redoing work or building up work in process, that’s not adding value. So if we take an attaché, and we know that attaché has 20 minutes of time that’s spent just adding value to that product, we can then measure our output in terms of minutes of work created against the amount of time that our workers worked. So we say, based on our time studies, our workers created 10,000 minutes of work today, but based on our time clock, they worked 20,000 minutes. That means they spent 50% of their time creating value. We measure this all the time. It enables us to get our pricing in check, enables us to know if we’re meeting our margins just by walking on the floor and seeing if there is work in process or if there are people moving around. It’s created goals for everybody to know whether the shop is LEAN and creating value or not.

Now, when we started this process, before we did any LEAN stuff, we were adding value only 20% to 25% of the time. The rest of it was all spent on non-value-added work. By the end of the process, we were adding value about 65% of the time, so our productivity almost tripled. It was difficult for most of our line workers to grasp the concept of what we were trying to sell to them, so we changed our measurement from percentage of time working efficiently (or adding value) to hours per day, and then people finally started to get it. We said, hey, you know, believe it or not, you’re only spending about two hours a day sewing, but you’re getting paid for eight. We’re asking you to spend about five and half to six hours sewing and get paid for eight, and they got it. That actually seemed like a great bargain to them. We were able to retrain everybody on LEAN principles; we made our own videos highlighting about 50 different non-value-added tasks that were regularly performed in the factories, so we could help people identify them.

Mark Graban: There are many things that are interesting and impressive about your story, but I think one of them is your involvement as an owner. LEAN is not just an operations strategy; it really is a key piece of your business strategy—it’s how you’re running the business and trying to be successful in the long term.

Mitch Cahn: Yeah, I think if I were to describe my job, I’m in charge of LEAN here. Everything else kind of takes care of itself, but LEAN is a battle against human nature, and it constantly needs improvement. If you’re doing LEAN properly, you need to continually improve, because if you are able to clear up one bottleneck, there’s going to be another bottleneck created somewhere else. You clear up that bottleneck in sales, and there’s going to be a bottleneck in production. You clear up that bottleneck, then you find a bottleneck in order processing. So I leave the top line growth up to the salespeople, and I take care of the growth and capacity by implementing LEAN principles throughout our entire organization.

Mark Graban: At the conference you displayed hats you’d produced for Jeb Bush and for Hillary Clinton, and there was the bright red, very familiar Donald Trump “Make America Great Again” hat. I was wondering if there were any stories, particularly behind the Trump hat. I’m curious about getting that business and trying to deliver a large number of hats relatively quickly. Are there any stories that you can share about that?

Mitch Cahn: As for Hillary Clinton’s campaign, we have been doing work for a company called Financial Innovations for decades. They’ve been managing the Democratic candidates for President for quite some time, ever since Bill Clinton. We have a very strong relationship with them. One of the reasons our company is regularly chosen to produce products for candidates is that we can produce goods quickly. Candidates don’t buy for the long-term—a lot of the primary candidates right now don’t know if they’re going to be around in two or three weeks, so they’re ordering every week. Instead of ordering 25,000 hats at a time, they’re ordering 2,000 or 3,000 hats a week. They need people who can turn things quickly, and because of our LEAN principles we can do that. We don’t have a lot of work in process on the floor, so we’re able to rush orders for people who need them. Another reason is that we’re a union shop, and the union label assures political campaigns that we’ve already been vetted for any sort of social compliance issues. That’s a smaller issue for the Republican side, though we have done a ton of Republican work. We did all of the work for the John McCain campaign, and we’re doing about four candidates right now. They just ask that we don’t put a union label inside the hat, for whatever reasons.

The second reason that we’re chosen is that we have a reputation. The candidates don’t want to get bitten by going to unknown manufacturer and finding out the products were actually made overseas. Our reputation as a military contractor says to them that we have been vetted by the military, and military goods need to be made domestically—not just all the labor but even all of the components for those products need to be sourced domestically. So I think that’s why they come to us. We never work with the campaigns directly; we always go through advertising agencies. The particular agency that we worked with on the Trump hat came to us from the Made in USA Foundation. They were concerned after they’d seen these hats being made overseas and contacted that agency, who told them that they don’t need to put “Make America Great Again” on a hat that says Made in China.

Mark Graban: Right. It’s interesting that of the three hats that were on display, the Trump hat was the only one that did not have Made in the USA embroidered on the brim. I think some people misunderstand LEAN as being about cost, when the primary thing is about improving flow, as you’ve described so well here—reducing setup times, improving productivity as a way of being more responsive to customers. Those are really powerful things, and they can lead to being cost-competitive, as it seems you’ve done at Unionwear.

Mitch Cahn: Yes, it has, and in many ways that you wouldn’t anticipate. LEAN has developed our dedication to measuring time and doing value stream maps for nearly every product that we manufacture. Our production process is data-driven. Over the last five years, much of our business has been re-shoring, where companies, usually in the fashion or promotional industry, have been getting products made overseas but are starting to reconsider. In the past, our hats might have been ten times as much as the hat made in China, but now they’re only 25% or 30% more. Companies are much more likely to switch now, so we’re constantly getting products that have been manufactured overseas, and we’re asked to quote on them for domestically made product. We look at the way these products are made overseas, perhaps in China, and it doesn’t make any sense to us. Take a tote bag for example—they throw labor at it to save on materials. It’s a dead giveaway when I see a tote bag that has a seam running along the bottom. If you cut that tote bag in two pieces, you’re going to get a lot more bags out of the roll of fabric than if you cut one big piece, but it adds a lot of labor and makes it a weaker bag. It makes no sense unless you’re trying to save on materials.

So we take these products and we reengineer them in a way that is LEAN and uses the least amount of labor possible. Between our productivity increases and our ability to reduce the amount of labor that goes into the product, we’re able to compete on many items, particularly in the fashion business.

Mark Graban: I really appreciate you being able to share your story both at the Northeast LEAN Conference and for taking time to talk with me here today, Mitch. Again, my guest has been Mitch Cahn, President of the company, Unionwear. Mitch, I was wondering if you want to talk about the company’s website, or ways people can learn more about your business, or if you have any final thoughts for the listeners.

Mitch Cahn: Sure, our website is unionwear.com. We have over 40,000 Made in USA products that you can search for and order directly on the website. You can contact me through the website if you have any questions about LEAN. I love helping other manufacturers who are just getting started in the LEAN process. I just want to warn you—it’s never a good time to start, but once you start, you will be rewarded. You’ll never finish, but you will be continuously improving.

Mark Graban: Well said, and thank you, Mitch, for that final thought and for being a guest here today on the podcast, I really appreciate it.

Mitch Cahn: You’re welcome. Thanks.

Introducer: Thanks for listening. This has been the LEAN Blog podcast for LEAN news and commentary updated daily is at www.leanblog.org. If you have any questions or comments about this podcast, email Mark, at leanpodcast@gmail.com.

Dad Caps

Dad Caps

Five Panel Hats

Five Panel Hats

Mesh Back Hats

Mesh Back Hats

In Stock Blanks

In Stock Blanks

Snapback Hats

Snapback Hats

Stretchfit Hats

Stretchfit Hats

Duffel Bags

Duffel Bags

Backpacks

Backpacks

Tote Bags

Tote Bags

Computer Bags

Computer Bags

Sling Messenger Bags

Sling Messenger Bags

Cooler Bags

Cooler Bags

Cuff Hats

Cuff Hats

Beanies

Beanies

Scarves

Scarves

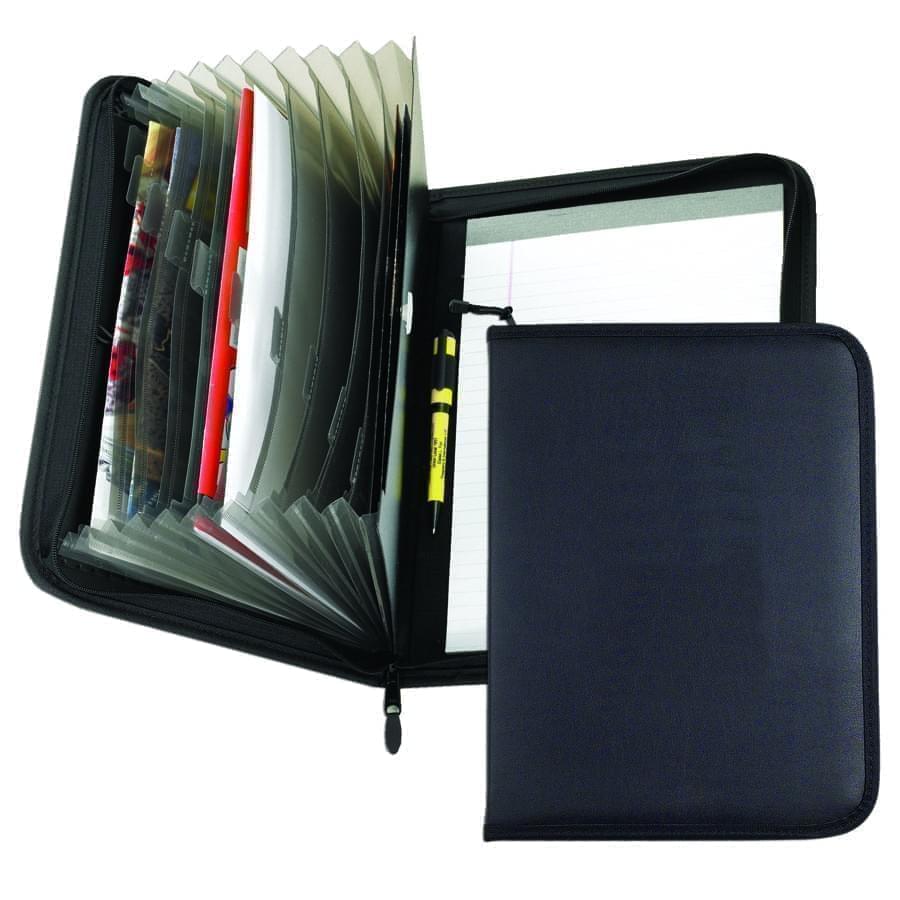

Zipper Folders

Zipper Folders

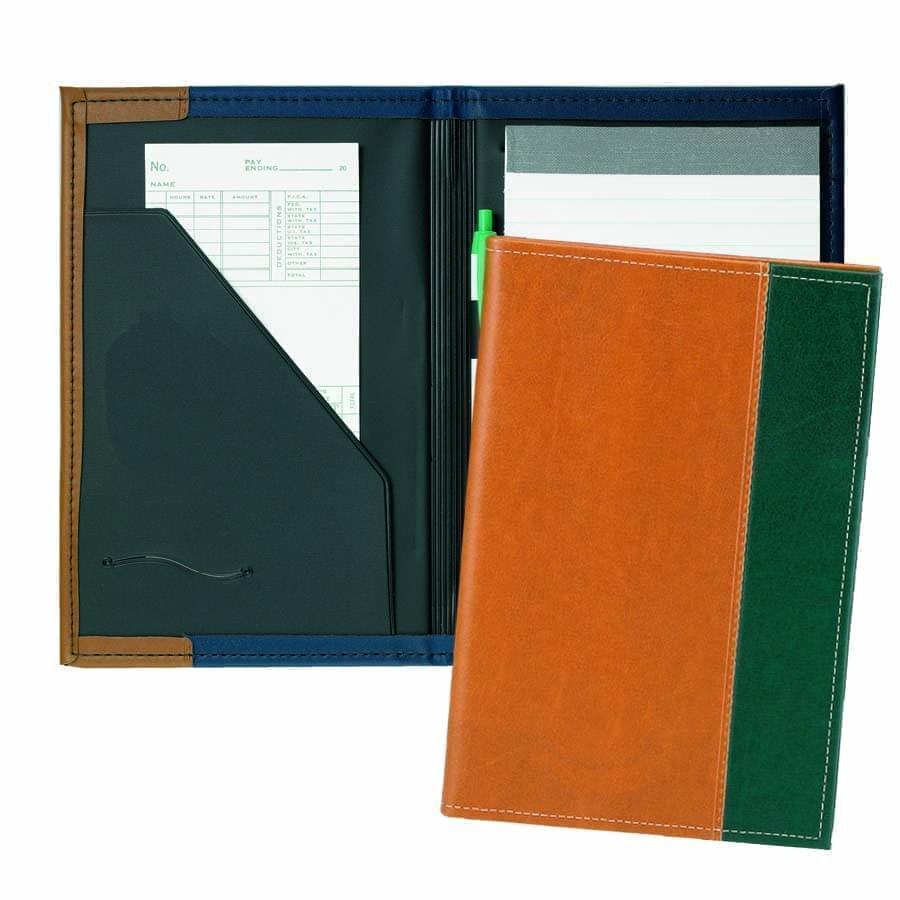

Stitched Folders

Stitched Folders

Accordion Folders

Accordion Folders

Ring Binders

Ring Binders

Letter Folders

Letter Folders

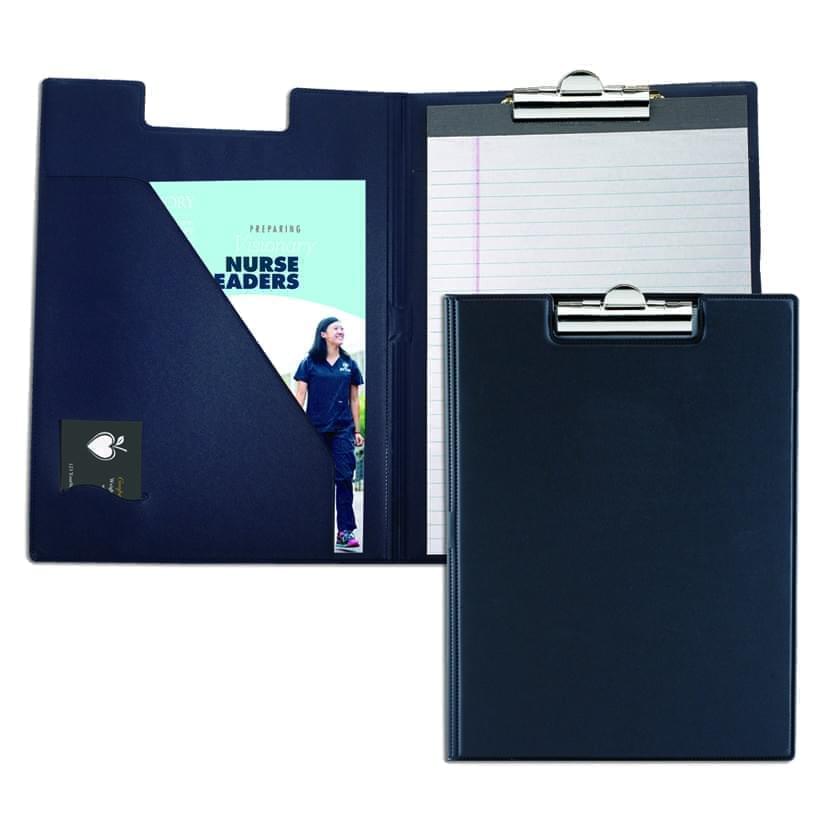

Clipboards

Clipboards

Union Made In USA

Union Made In USA