BROOKINGS INSTITUTION Metropolitan Innovation Series

Last month, manufacturers gathered at the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT) in Newark for a roundtable with government officials, educators, and industry leaders. The event spotlighted Essex County manufacturing partnerships and incentive programs and featured testimonials by companies such as Unionwear, which produces hats and bags in Newark’s North Ward. Otis Rolley, chief executive officer of the Newark Community Economic Development Corporation, told attendees about the resources available to manufacturers seeking to grow within Newark’s borders.

Meanwhile, at Newark Liberty International Airport on the other side of the city, students and faculty from Rutgers Business School were running a kiosk that sells merchandise made by New Jersey artisans and small manufacturers. The kiosk project, called Jersey Bound, complements the work of the Newark Industrial Solutions Center, which is housed at the business school’s Center for Supply Chain Management.

The zeal for product development and manufacturing has deep roots in Newark. For over a century, the city was a pioneer in America’s adoption of new industrialized methods and a production-based economy. Numerous products of global importance were invented in the Newark area, including Thomas Edison’s light bulb and air conditioning. These transformative breakthroughs and favorable policy and regulatory conditions contributed to rising incomes and improved economic security for a growing, skilled middle class. Yet, in recent decades, this knack for scientific discovery and making things has not translated into a more competitive production base and workforce.

Today, the 24-square-mile city of Newark is home to 400 manufacturers employing roughly 10,000 workers, and the greater Newark area is a base for 800 manufacturers, a diverse mix of small and mid-sized businesses largely serving regional markets. Despite some bright spots, greater Newark manufacturing is underperforming on employment and output metrics, as well as on the assimilation of appropriately skilled workers and tools that support product and process innovation. The unfortunate result is that Newark is failing to leverage a host of advantages that could favor small-scale production by design and manufacturing start-ups or by retooled, existing businesses. These advantages include density, ample industrial building stock, proximity to markets and service providers, and enviable logistical assets, including a globally connected airport and the largest maritime complex on the East Coast, Port Newark-Elizabeth.

Encouragingly, the city’s higher education institutions show signs of a focused commitment and invigorated strategies behind next-generation design, research and development, and production, as well as support for manufacturing-career readiness in areas ranging from robotics and digital design to technical operations management and market analysis. There are few manufacturing naysayers in the classrooms or around the seminar tables of University Heights—home to the Rutgers Business School as well as NJIT— or at nearby Essex County College or Newark Tech High School, but rather a growing focus on hands-on learning and industry-centered partnerships. Perhaps the boldest example of this activity is the launch last year of NJIT’s New Jersey Innovation Institute, which strives to align industry, educational, and economic development goals through partnerships and strategic clusters.

The challenge (and opportunity) that University Heights now faces is ensuring that the fruits of its initiatives and collaborations reach the area’s neighborhoods and residents, including through the reactivation of older industrial sites and locally embedded training options. Another key will be stemming the brain drain of qualified students out of the area. These goals are becoming increasingly critical in light of sweeping demographic shifts, including an aging industrial workforce and a youth unemployment crisis, as well as the need for infrastructure upgrades and strategies to manage transformation associated with the ongoing expansion of Port Newark-Elizabeth.

Through inclusive and sustained coordination as well as smart investment, a robust industrial commons is within Newark’s reach—an industrial commons that would make hometown hero Thomas Edison proud.

Nisha Mistry is director of the Urban Law Center at Fordham Law School in New York City. Previously, she served as a visiting fellow at Rutgers Business School and manufacturing advisor with the Department of Economic & Housing Development in Newark, N.J. under the administration of Mayor Cory A. Booker. From 2012 to 2014, Mistry served as a mayor’s office fellow (Office of Mayor Cory A. Booker) and nonresident fellow with the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program, where she authored a report on manufacturing in Newark.

SOURCE: http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/the-avenue/posts/2015/06/24-newark-higher-ed-manufacturing-mistry#.VYv-FCUXbWI.twitter

Dad Caps

Dad Caps

Five Panel Hats

Five Panel Hats

Mesh Back Hats

Mesh Back Hats

In Stock Blanks

In Stock Blanks

Snapback Hats

Snapback Hats

Stretchfit Hats

Stretchfit Hats

Duffel Bags

Duffel Bags

Backpacks

Backpacks

Tote Bags

Tote Bags

Computer Bags

Computer Bags

Sling Messenger Bags

Sling Messenger Bags

Cooler Bags

Cooler Bags

Cuff Hats

Cuff Hats

Beanies

Beanies

Scarves

Scarves

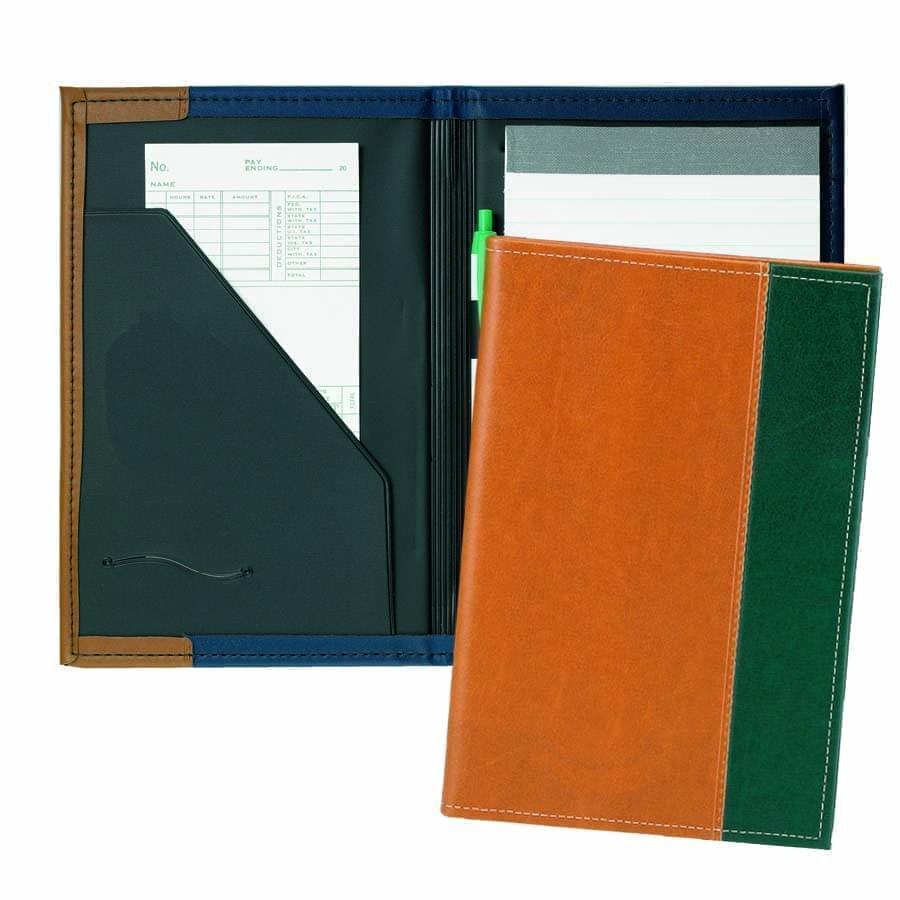

Zipper Folders

Zipper Folders

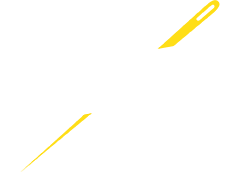

Stitched Folders

Stitched Folders

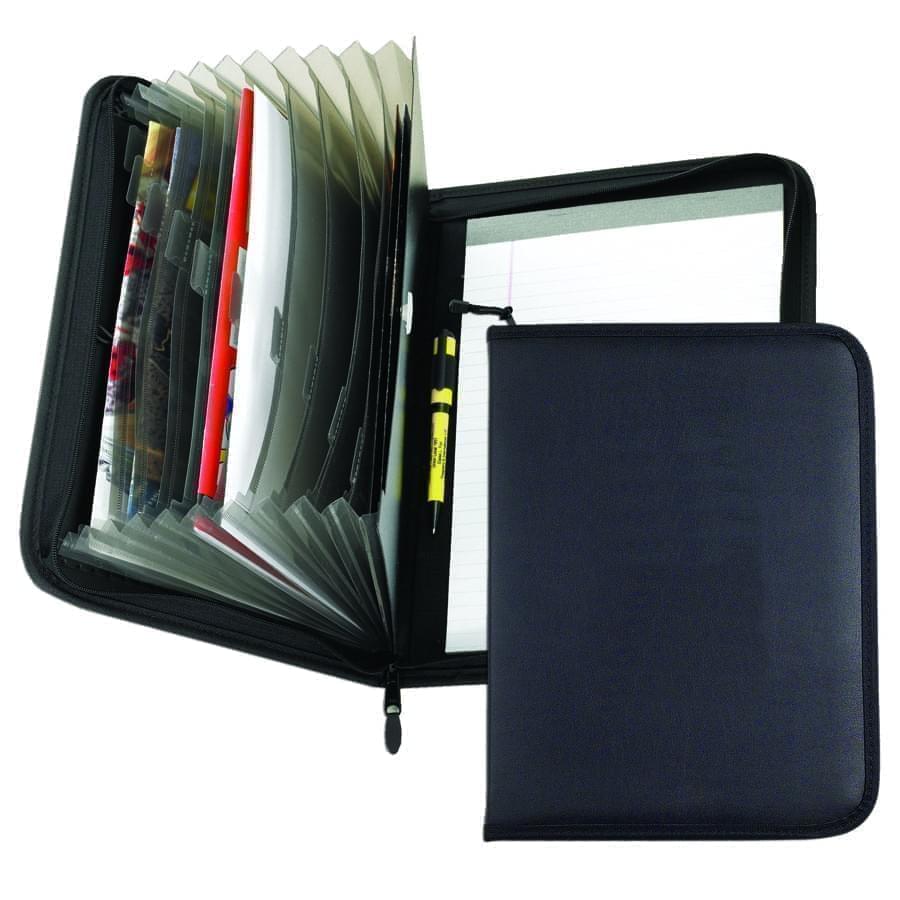

Accordion Folders

Accordion Folders

Ring Binders

Ring Binders

Letter Folders

Letter Folders

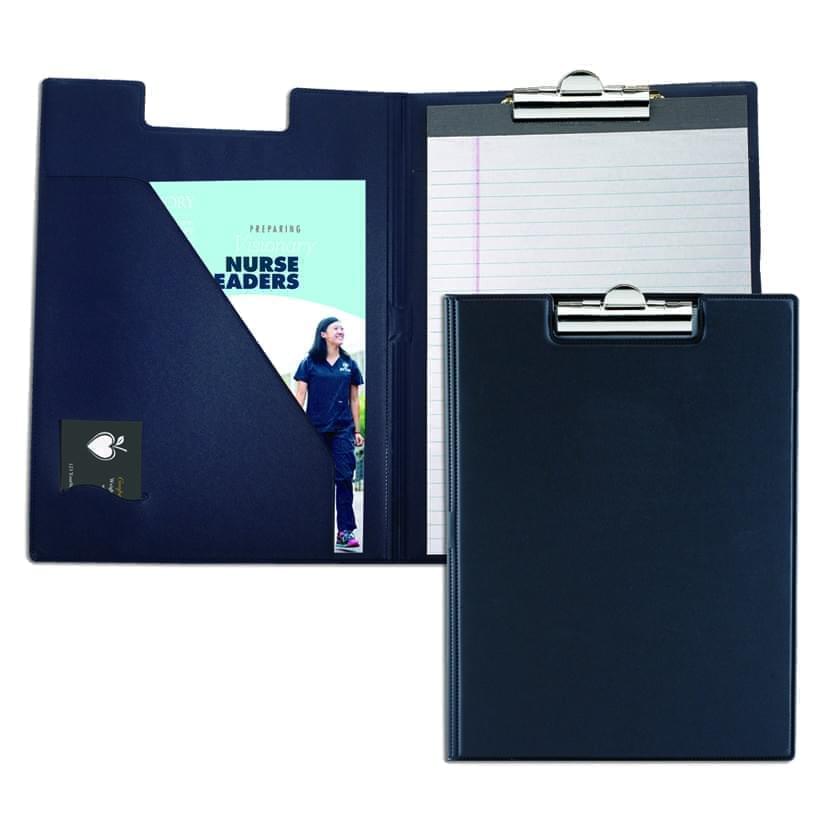

Clipboards

Clipboards

Union Made In USA

Union Made In USA