Mitch Cahn, president of the New Jersey-based supplier, says political hat sales can indicate the popularity of a candidate, noting that sales spiked after the Democratic presidential ticket changed.

Some say the design originated from a meme referencing popstar Chappell Roan, who sells a camo hat with orange lettering that says, “Midwest Princess.” Others say it targets rural voters who may sport camo regularly, as the former Minnesota Gov. Walz is a hunter.

Whoever the target demographic, the hat was a hit.

Cahn founded Unionwear in 1992 with six employees. One of the first orders the Made-in-the-USA manufacturer received was from Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign for 150 baseball hats.

“There was really no way for political campaigns to sell merchandise,” Cahn says, describing how political merchandise functioned more as a giveaway than a source of income in the pre-internet era. “The first time we really did substantial numbers, like six figures of units, was in 2000 with Al Gore.”

The Al Gore-Joe Lieberman ticket was the first campaign to set up an e-commerce merch website, Cahn says, and Unionwear’s hats were its primary item. Since then, the supplier has produced hats for candidates in every presidential election.

Unionwear gears up for election years. Anticipating demand for political merchandise, it tells its usual clients to avoid ordering in the summertime, updates its machinery and invests in additional employees and subcontractors.

In the early months of this campaign, Cahn says, it didn’t seem worth it.

“Sales were basically anemic,” he says. “We already decided, ‘You know what? This is not going to be a big presidential year.’”

Before President Joe Biden dropped out of the 2024 election, he was losing in his rematch with former President Donald Trump – and hat sales showed it.

Though there are nuances that can affect hat sales, like a candidate running again and people already having their merch, or a candidate taking advantage of free marketing by unofficial vendors, Cahn says he can measure the popularity of a candidate by those numbers. When Hillary Clinton was projected to win the 2016 election by a landslide, the merchandise sales didn’t match up, and Cahn wasn’t sold. (Contrast that with the high-profile popularity of Trump’s MAGA hats at the time.)

“We kept reading all the articles … that basically gave Trump no chance of winning the election, and we basically reconciled those things by saying, ‘Maybe Hillary’s supporters just don’t like baseball hats,’” Cahn says. “Turns out that was probably a pretty good indicator of how well the candidate was going to perform.”

Based on that metric, Biden was not performing well. Based on other metrics, his Democratic colleagues agreed.

Following the debate between Trump and Biden on June 28, Democrats were panicked. An increasing number of politicians called for the president to drop out, while others scolded the mutiny for not sticking by their candidate. As the chaos unfolded, Cahn hedged his bet.

“When I saw the debate, I met with the team and I said, ‘I really believe he is going to drop out of the race,’” he says. “‘If Kamala takes over, we’ll have an opportunity to sell a lot of merchandise.’”

Unionwear hit the ground running, building up inventory of blanks based on the merchandise the Harris campaign sold in 2020. When Biden officially dropped out in July, Cahn contacted distributors, campaign merchandise managers and convention groups, and orders started flowing in.

“This is a few weeks before the camo had dropped. We had already sold more merch than we anticipated selling for Biden the entire year,” Cahn says. “I didn’t think that there was going to be another kind of explosion.”

When the camo hat was released, Harris’ hat sales surged in popularity as she campaigned across the country. The numbers, Cahn says, are telling.

“They just picked a great design that resonated with a lot of people,” he says. “Baseball hats are definitely a great barometer.”

Dad Caps

Dad Caps

Five Panel Hats

Five Panel Hats

Mesh Back Hats

Mesh Back Hats

In Stock Blanks

In Stock Blanks

Snapback Hats

Snapback Hats

Stretchfit Hats

Stretchfit Hats

Duffel Bags

Duffel Bags

Backpacks

Backpacks

Tote Bags

Tote Bags

Computer Bags

Computer Bags

Sling Messenger Bags

Sling Messenger Bags

Cooler Bags

Cooler Bags

Cuff Hats

Cuff Hats

Beanies

Beanies

Scarves

Scarves

Zipper Folders

Zipper Folders

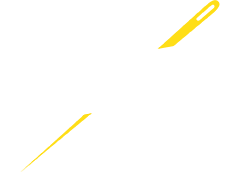

Stitched Folders

Stitched Folders

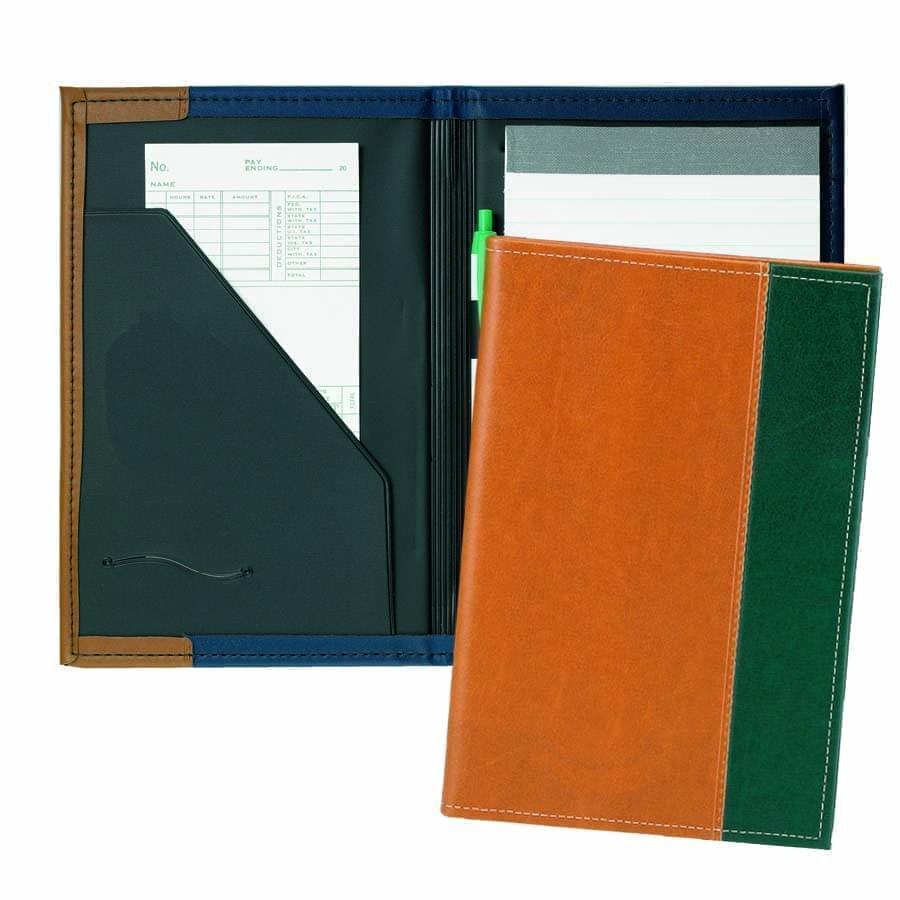

Accordion Folders

Accordion Folders

Ring Binders

Ring Binders

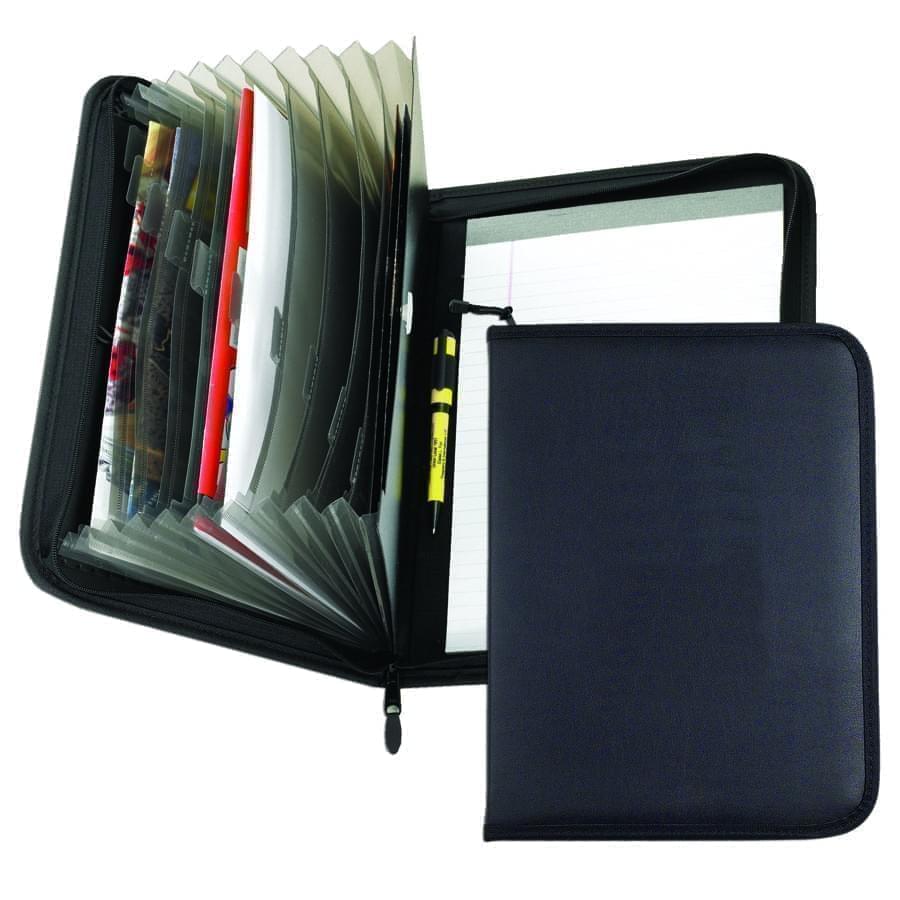

Letter Folders

Letter Folders

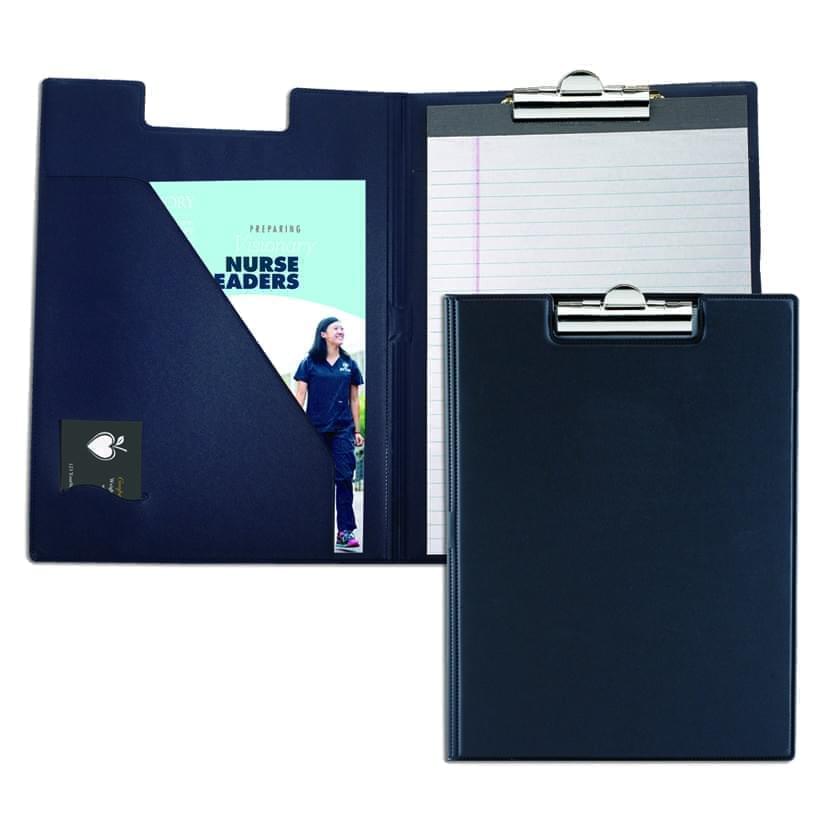

Clipboards

Clipboards

Union Made In USA

Union Made In USA