Mitch Cahn is the owner and founder of Unionwear, an apparel and accessories maker—all exclusively made in the U.S. Despite years of panicked manufacturing headlines—Japan is making everything! No, It’s China!—Cahn has kept his business open for 21 years and counting, all on American soil.

The company’s first core customers were unions that wanted to support union wages and “Made in USA” goods. Then more recently, a new crop of customers began ringing Unionwear headquarters in Newark, N.J.

East Coast fashion designers—including those in NYC’s garment district—were shopping for U.S.-based contract manufacturers. With labor costs in China rising and that country’s own economy accelerating, small U.S. shop owners couldn’t get the attention of overseas manufacturers. In an ironic twist, they couldn’t afford a “Made in China” strategy.

“Now we have five to 10 callers a day about doing that kind of contract work. It’s a groundswell,” Cahn said. “And it’s not patriotism. It’s economics that’s prompting them to call us,” he said.

Cahn’s changing business points to the shifting global economy. With labor costs in China forecast to climb further, more small-business owners are benefiting from, or actively pursuing, domestic manufacturing rather than overseas options, sometimes called reshoring.

And small shop manufacturers aren’t just dusting off shuttered businesses, locked up after jobs moved to countries such as Japan in the 1970s. Young entrepreneurs are innovating from scratch, creating new online communities such as Maker’s Row—and even turning to emerging platforms such as crowdfunding—to bankroll U.S. manufacturing operations.

(Read More: Made in the USA: More Consumers Buying American)

After Bangladesh

After the deadly collapse of a garment factory building in Bangladesh, more people have been asking questions about overseas-made apparel, often linked to sweatshops and unsafe working conditions. (Read More: How to Bring Ethics to Your Closet)

Some top European apparel labels includingH&M have signed a safety-standards pact. But other major U.S. companies including the Gap and Walmart are pursuing independent solutions. They haven’t signed the group safety accord, which binds retailers to improve safety at Bangladesh factories.

But searching for ethically-sourced goods in a global economy is tricky. And what percentage of a good’s raw materials and labor must originate from the U.S. to merit a “Made in the USA” label?

“Right now there’s no common, national definition for ‘Made in the USA,’ ” said Harold Sirkin, a senior partner at Boston Consulting Group.

Even if you wanted to make American-made products, sourcing domestic raw materials is challenging in part because most online manufacturing resources are Asia-focused. But one Brooklyn, N.Y.-based start-up is changing that trend.

(Read more: The ‘Opportunity’ Entrepreneur Returns)

Maker’s Row

Maker’s Row is an online matchmaker that connects designers with industry-specific factories and suppliers—all based in the U.S. Product designers and small businesses can join the website for free, while manufacturers pay $200 a month.

Maker’s Row founder Matthew Burnett is a designer and Detroit native. He relocated to New York City to work for major apparel labels, before launching his own watch line. His grandfather was a watchmaker so he’s been around small shop manufacturing all his life.

But manufacturing his designs overseas was a costly headache. Orders and tweaks, shipped abroad, took weeks to resolve. “You add import taxes and it becomes such a gamble manufacturing overseas as a small business,” Burnett said.

Maker’s Row was launched in 2012 and breaks down the manufacturing process for small- to medium-sized ventures. The site allows entrepreneurs, many first-timers, to plug into a U.S. supply chain including factories in all 50 states.

Participating businesses straddle apparel and accessories. “It’s harder to find a manufacturer in the U.S. than in China,” Burnett said. Maker’s Row plans to add other industries, and is wrapping up their seed round of funding.

The site includes about 10,000 small-business owners and roughly 1,800 manufacturers, including Cahn of Unionwear.

And a vibrant U.S. manufacturing sector means more domestic jobs. For a $1 million backpack order, for example, Cahn estimates he’s able to hire 35 to 40 New Jersey workers. Less than 10 percent of American jobs come from manufacturing.

(Read More: US Manufacturing Shrinks for First Time in Six Months)

Of course not everyone can afford American-made goods. U.S. consumer spending fell in April for the first time in almost a year, as personal income growth was flat. But attitudes are changing.

Earlier this year, Walmart announced it will boost sourcing of U.S. products. And more American and Chinese consumers are willing to pay a 10 percent to 60 percent premium for “Made in USA” goods, according to BCG research released last fall.

Meanwhile, a shift in manufacturing away from China will begin to take hold around 2015, according to BCG forecasts. Rising labor prices there will create a ripple effect.

Certain industries—in which labor is a lower percentage of total product costs—are more likely to pack up overseas for North America, including Mexico, where labor costs are stable. Product categories likely to reshore first include appliances and electronics, transportation, machinery, plastics, furniture and chemicals, BCG’s Sirkin said.

But as the global economy evolves and shakes out new winners and losers, consumers are connecting the dots between inexpensive, overseas goods and evaporating U.S. jobs.

The recession has been especially brutal on chronically out-of-work or underemployed Americans. Unemployment that counts the discouraged and underemployed, sometimes called the “real” jobless rate, is still above 10 percent in many states.

“People used to thumb their nose at manufacturing jobs,” said Unionwear’s Cahn. But when the recession gripped the U.S. and the manufacturing sector was among the first to stand up and create jobs, many gave the sector a another look.

“As a country we can’t all be servicing each other,” Cahn said. “You have to have manufacturing.”

—By CNBC’s Heesun Wee; Follow her on Twitter @heesunwee

Dad Caps

Dad Caps

Five Panel Hats

Five Panel Hats

Mesh Back Hats

Mesh Back Hats

In Stock Blanks

In Stock Blanks

Snapback Hats

Snapback Hats

Stretchfit Hats

Stretchfit Hats

Duffel Bags

Duffel Bags

Backpacks

Backpacks

Tote Bags

Tote Bags

Computer Bags

Computer Bags

Sling Messenger Bags

Sling Messenger Bags

Cooler Bags

Cooler Bags

Cuff Hats

Cuff Hats

Beanies

Beanies

Scarves

Scarves

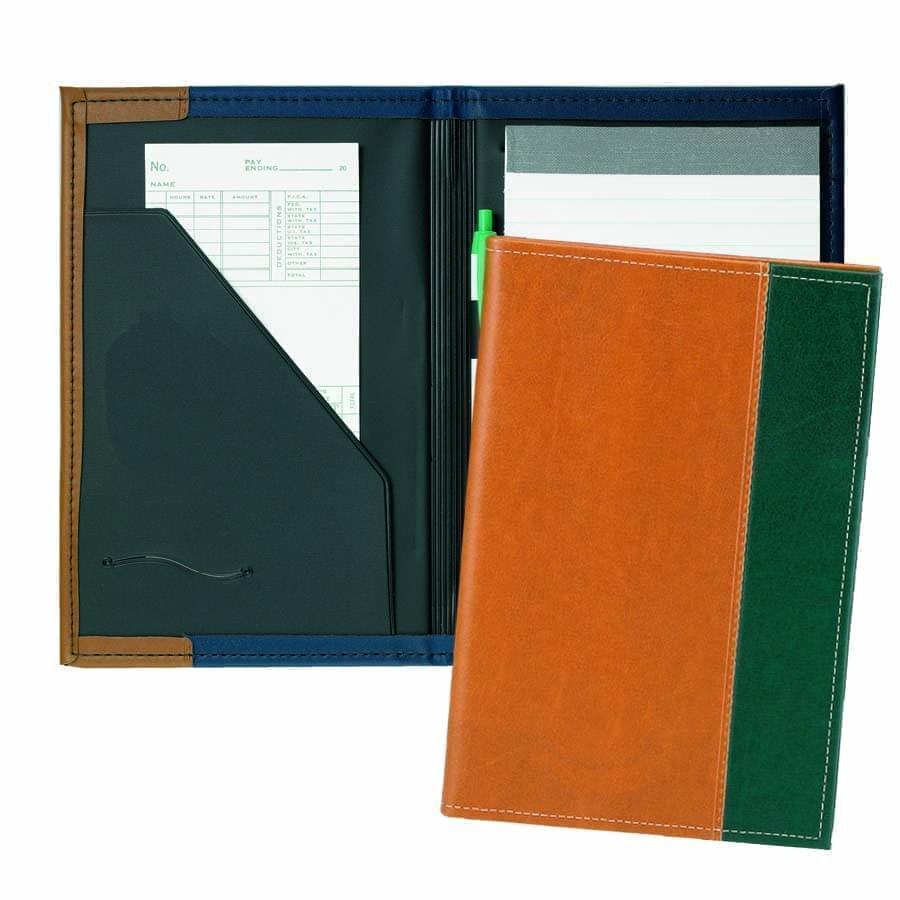

Zipper Folders

Zipper Folders

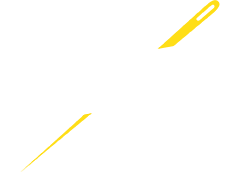

Stitched Folders

Stitched Folders

Accordion Folders

Accordion Folders

Ring Binders

Ring Binders

Letter Folders

Letter Folders

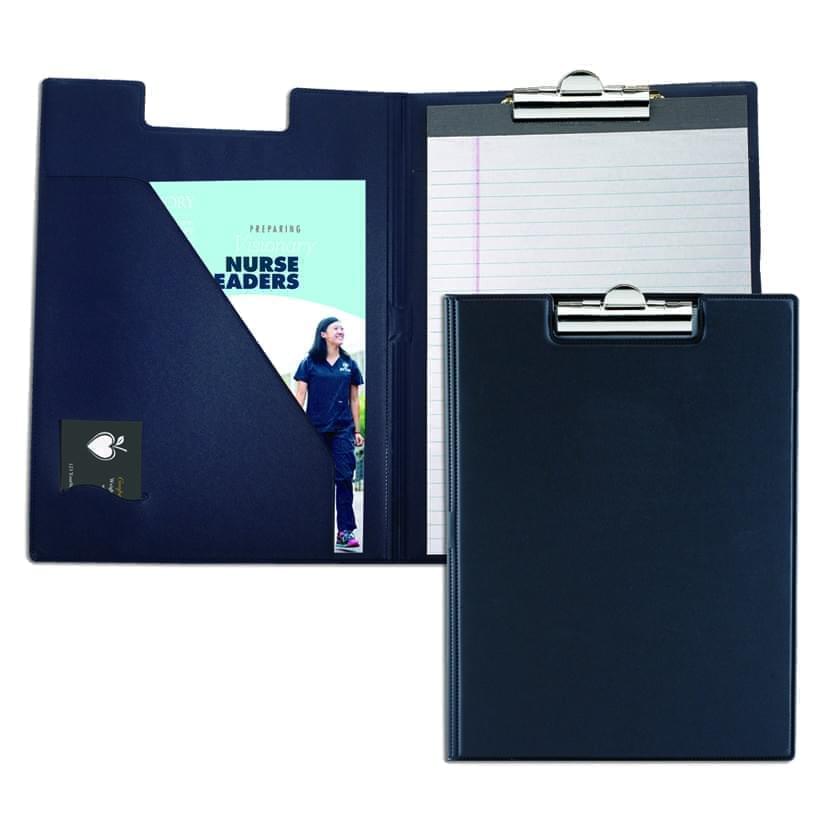

Clipboards

Clipboards

Union Made In USA

Union Made In USA