Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders aren’t exactly close on the political spectrum.

But at the Unionwear hat factory in Newark, New Jersey, they’re side by side.

Unionwear has been making campaign merchandise for US presidential candidates for nearly three decades.

The company caters to both Republican and Democratic candidates of all political stripes. This election cycle, the company has made campaign hats for Trump, Sanders, Joe Biden, Michael Bloomberg, and Elizabeth Warren, among other candidates.

Garment worker Maria Gallardo expressed a common sentiment: “We have to make money for our families, whether we agree or disagree with their message,” she said.

This year’s crowded field of candidates has been good for business. Cahn said Unionwear makes between 2,000 and 3,000 hats in a single day, with most orders coming from campaign-affiliated agencies or groups of supporters.

The 2016 election cycle was a particularly busy time for the company — Cahn said the company was surprised by demand for Trump’s famous “Make America Great Again” hats.

“Demand overwhelmed the supply,” he said. “And there are only a handful of factories in the United States. Everyone was working on that hat for Trump.”

Political campaigns often prefer merchandise companies that are based in the US, making Unionwear a go-to option.

Yet the candidate it’s provided the most merch for isn’t Trump, or Sanders, or even Bloomberg and his seemingly endless campaign budget.

That honor would go to Andrew Yang, the Democratic entrepreneur who dropped out of the race in February. Unionwear made many of the 30,000 “MATH” hats — that’s “Make America Think Harder — that Yang sold during his longshot presidential bid.

Its first political hats were for Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign.

Political swag is at least as old as the presidency itself — buttons bearing George Washington’s initials were sold at his first inauguration in 1789.

But the merch business really took off in the mid-1990s, when Cahn was just getting started with Unionwear.

Cahn started the business in 1992. His initial attempts to sell to high-end clients like Neiman Marcus and Ralph Lauren were successful but short lived when the garment industry started to migrate to China en masse in 1994.

“We were left with a baseball hat factory and a lot of employees,” he said. “And not a lot of places to get business from.”

He didn’t have to look far for new clients, though. He began selling to American unions, which were looking for products made by unionized businesses like his. He also began selling to military agencies, some of which are required to buy US-made products.

Then came the political campaigns, starting with a small order of 150 hats for Bill Clinton’s first presidential campaign in 1992. But Cahn said business didn’t really take off until Al Gore, then vice president, ran for president in 2000.

“We sold probably more hats than we had ever sold for any one particular client,” Cahn said. “It was probably 200,000 hats overall.”

All of Unionwear’s production takes place at its New Jersey plant. That makes the company an attractive option for political campaigns, who often want to hire US-based companies to make their merchandise.

Unionwear contributes to a multibillion-dollar political marketing industry. Campaign managers and political strategists are increasingly looking to merchandise like hats and other apparel as powerful branding tools, according to New York magazine. Trump’s campaign alone has made $45 million off his “MAGA” merchandise.

So what happens to Unionwear’s supply of hats once a candidate drops out, like Democrats Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg did recently?

“We have this down to a science. We are producing in small batches,” Cahn said. “Someone would have to drop out really unexpectedly for us to get stuck with anything.”

Dad Caps

Dad Caps

Five Panel Hats

Five Panel Hats

Mesh Back Hats

Mesh Back Hats

In Stock Blanks

In Stock Blanks

Snapback Hats

Snapback Hats

Stretchfit Hats

Stretchfit Hats

Duffel Bags

Duffel Bags

Backpacks

Backpacks

Tote Bags

Tote Bags

Computer Bags

Computer Bags

Sling Messenger Bags

Sling Messenger Bags

Cooler Bags

Cooler Bags

Cuff Hats

Cuff Hats

Beanies

Beanies

Scarves

Scarves

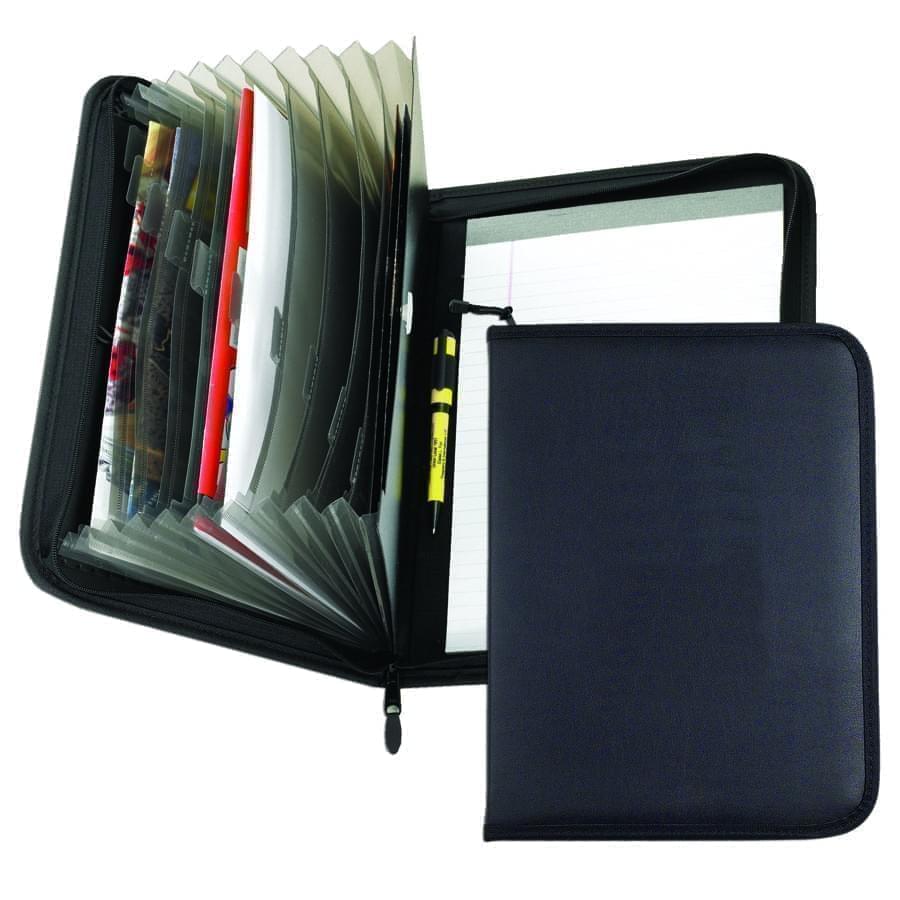

Zipper Folders

Zipper Folders

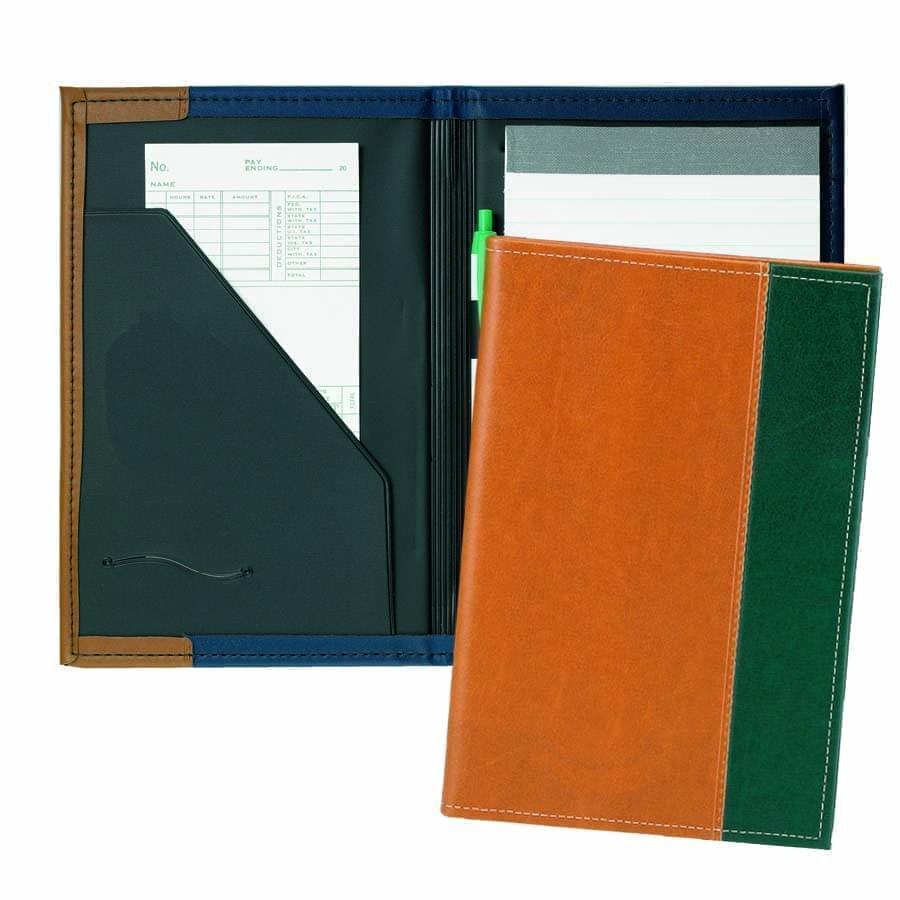

Stitched Folders

Stitched Folders

Accordion Folders

Accordion Folders

Ring Binders

Ring Binders

Letter Folders

Letter Folders

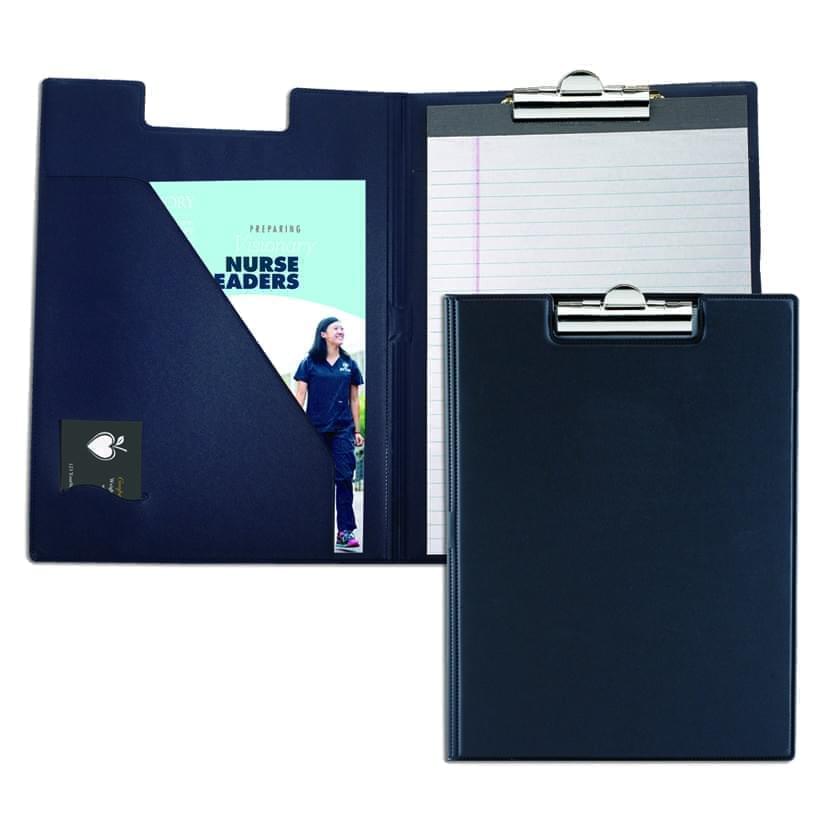

Clipboards

Clipboards

Union Made In USA

Union Made In USA