Buying America: The Many Astounding Ways You Can Express Your Values with Your Pocket Book

Shopping can be an ethical act.

By David Morris / AlterNet July 27, 2015

“Every person ought to have the awareness that purchasing is always a moral – and not simply an economic – act,” Pope Francis announced early this year. How can we spend our money as if our values matter?

In some sectors and for some values this is fairly easy. Food is an obvious example. Those who want to protect the environment and human and animal health will find abundant labels guiding them to the appropriate product: USDA Organic, free range, hormone free, grass fed. For those who want to strengthen community, shrink the distance between producer and consumer and support family farmers a growing number of grocery stores label locally grown or raised.

For those who want to support farmworkers as well as farmers, however, little guidance is available. The recently launched Equitable Food Initiative and Food Justice Certified labels hope to fill this gap. The former identifies food that has been harvested by workers paid a fair wage and laboring under safe and fair conditions. The latter offers three tiers of certification covering farm, processor and vendor/retailer. Only farms have been certified.

As for grocery stores, we can easily identify those cooperatively or locally owned. Going one step further along the supply chain we can use the Restaurant Opportunities Center United (ROC)’s Diners Guide to Ethical Eating downloadable app to identify restaurants that treat their workers well. Extra credit is given to non-chain businesses. To earn a favorable rating the restaurant must pay its non-tipped workers at least $10 an hour and tipped staff at least $7 an hour, grant all employees paid sick days and enable internal promotion.

The ethical consumer who wants to patronize a locally owned retail store in general can visit Independent We Stand and download its mobile app. Or go to AMIBA and BALLE to find a list of independent business alliances in over 100 cities many of which have hundreds and even thousands of individual member businesses.

There are few guides to locally and rooted manufacturers. But 3-year-old San Francisco Made offers an excellent model, interconnecting and nurturing its 325 member manufacturers located in that city.

The vast majority of products we purchase will come from regional and national firms. One can easily check to see if the company is American and sometimes that will be necessary even when we think we know from the product’s name what nationality the company is. As Roger Simmermaker, author of How Americans Can Buy American and My Country ‘Tis of Thee points out, “Swiss Miss is American (based in Menomonie, Wisconsin) and Carnation is owned by the Swiss.”

For those who want to go beyond where a company is headquartered to who owns it, a list of companies owned by their employees is available from the National Center for Employee Ownership.

Finding American made products as opposed to American corporations requires more legwork. Almost 8 in 10 American consumers say they prefer to buy American made products according to Consumer Reports. (Another survey found that for Americans ages 18-34 the percentage drops to 4 in 10.) Patriotic buying has gained considerable cache in the last few years and is beginning to change corporate behavior.

Consider this story of Florida orange juice. In 2007 Pepsi and then Coke began to mix oranges from other countries with Florida oranges. Florida’s Natural, an agricultural cooperative owned by 1100 growers, whose motto is “we own the land, we own the trees, we own the company” added a logo to its packages sporting an American flag and the words “Product of U.S.A.” For a few years Pepsi and Coke thought price would trump homegrown but in early 2012 the Tropicana Products division of PepsiCo began to proclaim in print ads, “Grown, picked and squeezed in Florida,” (Florida’s Natural responded with its own new tag line: “All Florida. Never imported. Who can say that?”)

A 2013 survey of more than 200 U.S.-based investors interested in the luxury sector, found 80 percent of them concerned that the reputational risk associated with offshore manufacturing is beginning to offset the cost savings for luxury goods manufacturers. After Ralph Lauren proudly unveiled its new uniforms for the U.S. team for the 2012 summer Olympics it was discovered that every piece of the uniform was made overseas. A considerable public backlash led the company to promise to make the U.S. uniforms for the 2014 Winter Games from USA components.

Mitch Cahn, the CEO of Unionwear, a Newark, New Jersey clothing manufacturer told John Oliver about why both Democratic and Republican candidates buy his company’s hats. “Both want to demonstrate their commitment to made in USA. Plus, whenever one of their vendors messes up and sources something from overseas or switches. When they get caught, which they invariably will, it’s going to cost them so much more money to fix the problem, backpedal, apologize, change their message, that it’s easier and cheaper to just patronize clean shops.”

Finding out if a product is made in the United States is easy. All imports must carry country of origin information on the outside of the package. Finding domestic products that are largely made of domestic components, however, may be more challenging.

How American Is That American Product?

Even if we buy American made how much of the value of the product is actually made in America? For automobiles, textiles, wool and fur products the law requires disclosure of the percentage of a product’s domestically produced content.

The 1994 American Automobile Labeling Act (AALA) requires all automobiles and trucks to prominently display a sticker showing the percentage of its value made in the United States. The AALA has several shortcomings. For one, it does not distinguish between Canadian and U.S. production. It does not take into account where the profits go (e.g. is the company foreign owned). Finally, it allows the “content percentages to be calculated on a “carline” basis rather than for each individual vehicle and may be rounded to the nearest 5 percent.”

The more sophisticated Kogod Made in America Auto Index, released annually by American University incorporates the (AALA) but adds seven further criteria: site of body, chassis, and electrical parts manufacturing (50 percent); site of engine production (14 percent); site of inventory and capital expense allocation (11 percent); site of transmission production (7 percent); site of assembly labor (6 percent); site of research and development (6 percent); and finally, where the profits in each aspect of the transaction go (6 percent).

In 2014 the Ford F-150 truck, the best selling vehicle in America topped the Kogod charts with 87.5 points out of 100.

As a general rule, automakers are more likely to build larger vehicles with higher profit margins in the U.S. and smaller ones overseas. The Kogod index seems to bear this out. The F-150 and Chevy Silverado score in the 80’s while the Chevy Spark and Ford Fiesta have scores of 15.5 and 19.5 respectively.

Aside from cars and textiles and furs, no U.S. supplier needs to identify where the product is made or its components. But if the company boasts that a product is “Made in the USA” or “Made in America” it must “contain no – or negligible – foreign content” according to regulations issued by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the product’s final assembly or processing must take place in the United States.

Nevertheless, the buyer who sees a Made in America sticker must still beware. The FTC investigates several complaints a year, almost all submitted by manufacturing competitors and the vast majority end in a settlement with no civil penalty. The civil penalties themselves are modest. California has its own higher and more rigidly enforced standard. No component of a product advertised as Made in the USA can be imported. In 2011 California’s Supreme Court ruled that the company Kwikset could be sued for using the label on one of its locks because the screws in it were manufactured in Mexico.

Americans don’t like to be misled by faux patriotic corporate advertising. As Consumer Reports notes, “Readers who have sent us complaints seem most irritated by foreign-made products whose makers have patriotic names (American Mills, Americana Olives, Great American Seafood, United States Sweaters, the U.S. Lock company) or whose packages have flag-waving slogans (“true American quality”) or symbols (pictures of the flag, eagle, Statue of Liberty).”

Over 90 percent of shoes and clothing sold in the United States is imported. One will almost always pay more to purchase Made in the USA but often their quality is far superior. If you buy a Brooks Brothers suit, 70% of which are made in Massachusetts, or tie, 100% of which are made in New York or shirt, 15% of which are made in North Carolina the quality is first rate and the clothes last considerably longer than cheaper imported items.

More than 97 percent of American denim jeans are made abroad but you can still find American made denim. In the 1990s Lawson Nickol was working for a U.S. jeans manufacturer who like almost all other jean manufacturers decided to move production to China. He resigned and in 2002 with his son BJ Nickol founded the All American Clothing Co. They started manufacturing their own clothing in 2007. Unique among jeans manufacturers, their customers can enter a code and trace their jeans back to the farm that grew the cotton.

One of the new firm’s biggest challenges was finding suppliers. “The apparel industry has lost 85 percent of cut and sew people in the USA since 2002 when China became king”, Nickol notes. He’s had to pay more for their materials and labor which makes their clothes more expensive which Lawson concedes but proudly adds, “…I buy a lot of higher cost products that are made in the USA in order to support tax base, jobs, SSN, police, firemen, hospitals, infrastructure, military, freedom, etc, etc. I don’t buy foreign jeans and help to support labor atrocities, child labor, poor manufacturing quality, give money to the foreign governments…”

Despite higher input costs his jeans prices are still competitive with denim giants like Levis. Why? “One of the things we don’t do a lot of is marketing and advertising,” says Nickol. American Clothing sells 95 percent of its products online. Nickol adds, “We don’t have as big of margins.”

Sluggish wages in the United States and soaring labor costs in countries like China, coupled with the growing realization of the costs inherent in the rigidity of long supply chains and the potential for product piracy, has made it increasingly possible to buy American in many sectors. Whirlpool already makes 80 percent of the products it sells in the U.S in its U.S. plants and it prices them competitively. In 2000, it manufactured most of its front-loading washers in Germany. Now the company is moving that production back to its Ohio-based facilities. “On the one hand, U.S. labor costs are often higher than in other countries,” says Whirlpool’s Casey Tubman. “But when you look at the higher productivity for American workers and consider the fact that it’s very expensive to ship something as big as a refrigerator or washer, we can quickly make up those costs.”

There are several useful web sites that identify American made products. (Look here, here, here, here, and here.)

Going Beyond Buy America

The same Consumer Reports 2013 survey that found that 78 percent of us prefer to buy American products also found that other values were equally or more important to us. Ninety-two percent preferred products from companies that give back to the local community; 90 percent preferred companies that treat their workers well; 82 percent prefer firms that express public support for causes we believe; 79 percent prefer a company that engages in environmentally friendly practices.

If you are one of the 90 percent who care how companies you want to buy from treat their workers one good indicator is whether the product is made with union labor. For clothing you can look for the UNITE label (the union created from the merger of the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees and the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union). Those seeking to buy a specific car made by union members can find a list here. Those seeking web sites that offer extensive links to union made products can go here and here.

Those wanting to know more generally about the character of the company with whom they are doing business can check out whether it is a Benefit Corporation. This new type of corporation is required to consider its impact not only on shareholders but also on workers, community, and the environment. Benefit corporations are required to make available to the public an annual benefit report that assesses their overall social and environmental performance against a third party standard. Twenty-eight states currently permit a corporation to become a Benefit Corporation. A list of Benefit Corporations by state is available here.

Certified B corporations are Benefit Corporations which must achieve a minimum verified score on an Assessment by B Lab, a 501©(3) organization. Recertification every two years is required against an evolving standard. A list of Certified B Corporations can be found here. About 60 percent are American corporations. Each year B Lab publishes a list of its top Certified Benefit Corporations by size and category. Companies are broken out by midsized, small, micro enterprises and sole proprietorships and are graded based on their environmental, worker and community impact.

For example, in 2014 King Arthur Flour and New Belgium were among the top rated B Corporations on labor issues. The 200 year old King Arthur, a company of 388 workers at the busiest times of the year, has a minimum hourly starting wage for full-time workers of $11.25 an hour. New Belgium’s lowest wage for non-temporary workers is $12 an hour. King Arthur Flour and New Belgium are 100 percent employee-owned companies. Both have profit sharing plans. At King Arthur Flour low income employees receive a heavily subsidized Community Supported Agriculture shares.

As Stephen Lurie at Vox observes, despite its high rating, King Arthur Flour puts its USDA organic label on the front of its packages and its B Logo on the back.

Assessing the character of a company is complicated and by its nature incomplete. Some might want to know how willing companies are to pay their fair share of taxes to sustain our public schools and roads and colleges. In 2015 Bloomberg compiled a directory of 299 companies detailing how much of their total profits they’ve stashed abroad to avoid taxes. Bizvizz has an ambitious but spotty downloadable app allows you to use your phone to take a picture of a brand and discover what tax rate the corporation that makes the product pays and in many cases, where its political contributions go.

Often those who want to make ethical purchases will have to assess which of the values they embrace are more important. For example, what do we buy when the organic farm treats its workers poorly? Would you choose a conventional tomato picked by well-treated workers than a local heirloom variety harvested by oppressed workers as the food writer and activist Eric Schlosser declared he would? Or would you choose the tomato that stresses the environment? A Toyota Camry is among those vehicles with the highest percentage of its components coming from the United States. But its plants are not unionized and the company’s profits do not stay in the United States.

With much fanfare Walmart has launched a new Buy America initiative. Would you now shop there given that Walmart’s policies may have single-handedly resulted in the outsourcing of hundreds of thousands of U.S. manufacturing jobs and the erosion of U.S. workers wages? Or that more than 20 years ago it launched a similar campaign and began hanging “Made in America” signs in its 750 stores until NBC’s Dateline offered significant evidence the initiative was “more an advertising gimmick than a substantial plan.” At the beginning of its current initiative Walmart publicized a contract with 1888 Mills, a Georgia towel maker to produce American-made towels for the company’s stores. But 1888 Mills, which has an overseas workforce of some 14,000, will be adding only 35 jobs low paid jobs at its U.S. factory to meet Walmart’s multi-year purchase agreement.

Sometimes different values can lead customers to the same supplier. As I noted above, both Democrats and Republicans buy their caps from Unionwear in election years to demonstrate their support for domestic jobs. John Oliver calls it “electoral jingoism”. But CEO Mitch Cahn points out one key difference between the political parties on their values beyond domestic sourcing, “Democrats brag about their products being union made and the republican don’t want anyone to find out about it.”

Dad Caps

Dad Caps

Five Panel Hats

Five Panel Hats

Mesh Back Hats

Mesh Back Hats

In Stock Blanks

In Stock Blanks

Snapback Hats

Snapback Hats

Stretchfit Hats

Stretchfit Hats

Duffel Bags

Duffel Bags

Backpacks

Backpacks

Tote Bags

Tote Bags

Computer Bags

Computer Bags

Sling Messenger Bags

Sling Messenger Bags

Cooler Bags

Cooler Bags

Cuff Hats

Cuff Hats

Beanies

Beanies

Scarves

Scarves

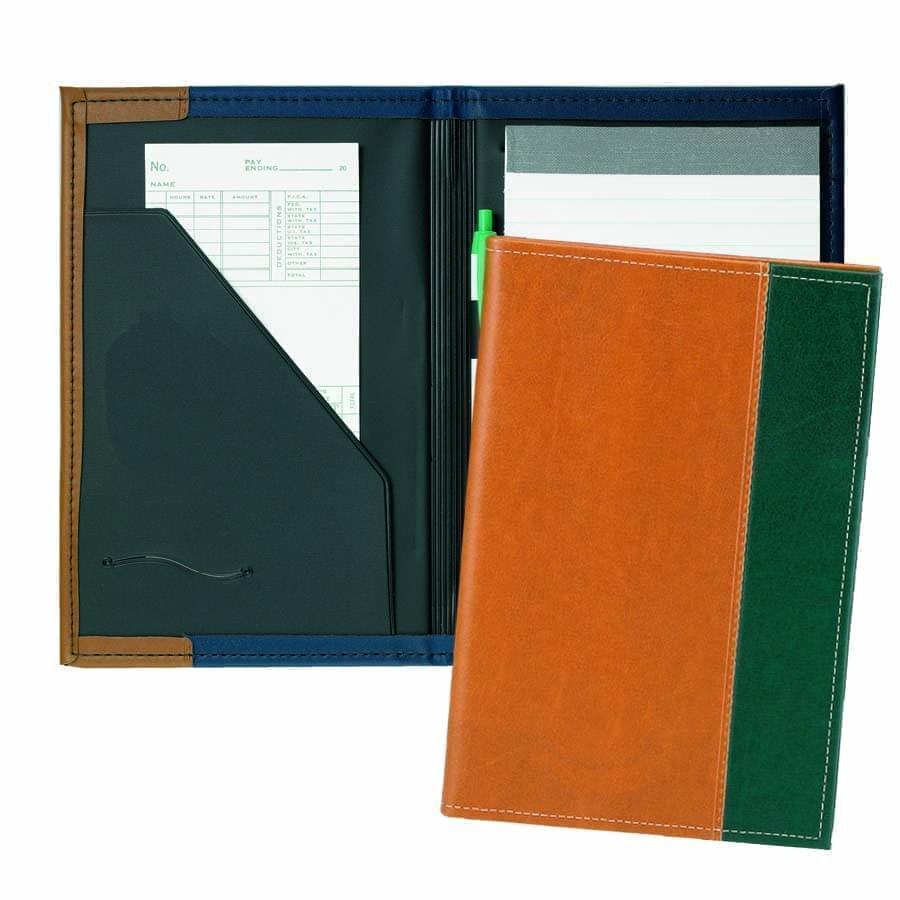

Zipper Folders

Zipper Folders

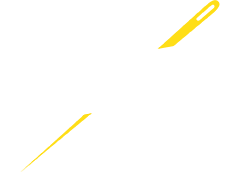

Stitched Folders

Stitched Folders

Accordion Folders

Accordion Folders

Ring Binders

Ring Binders

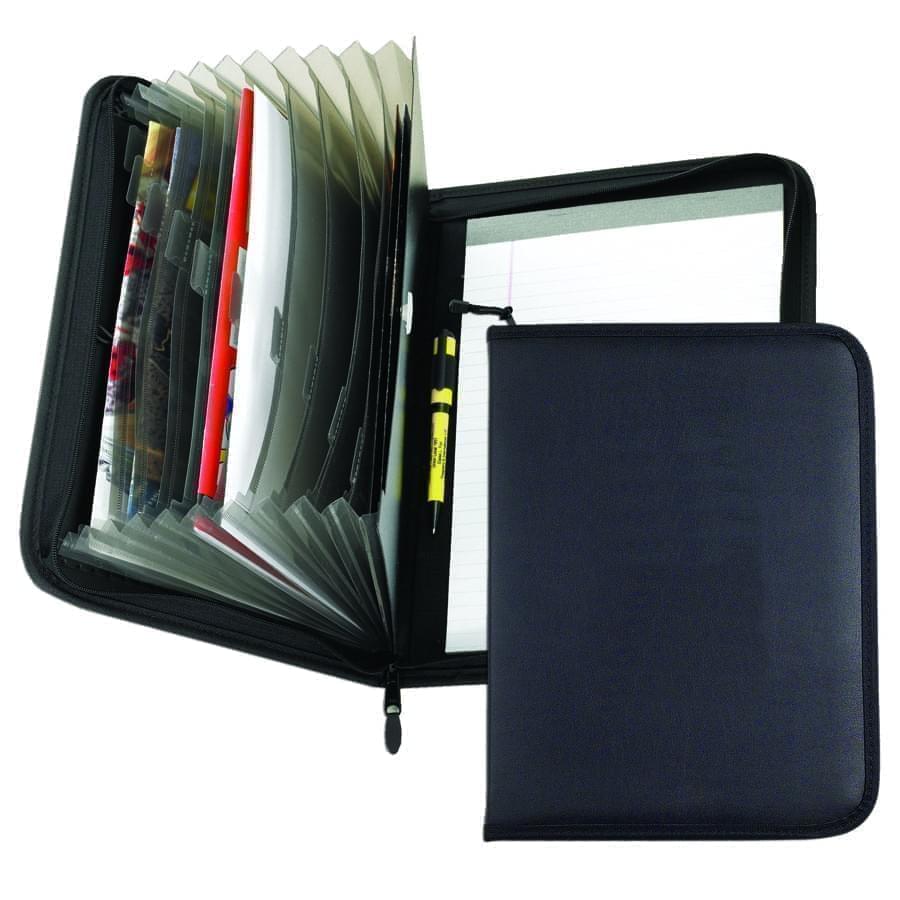

Letter Folders

Letter Folders

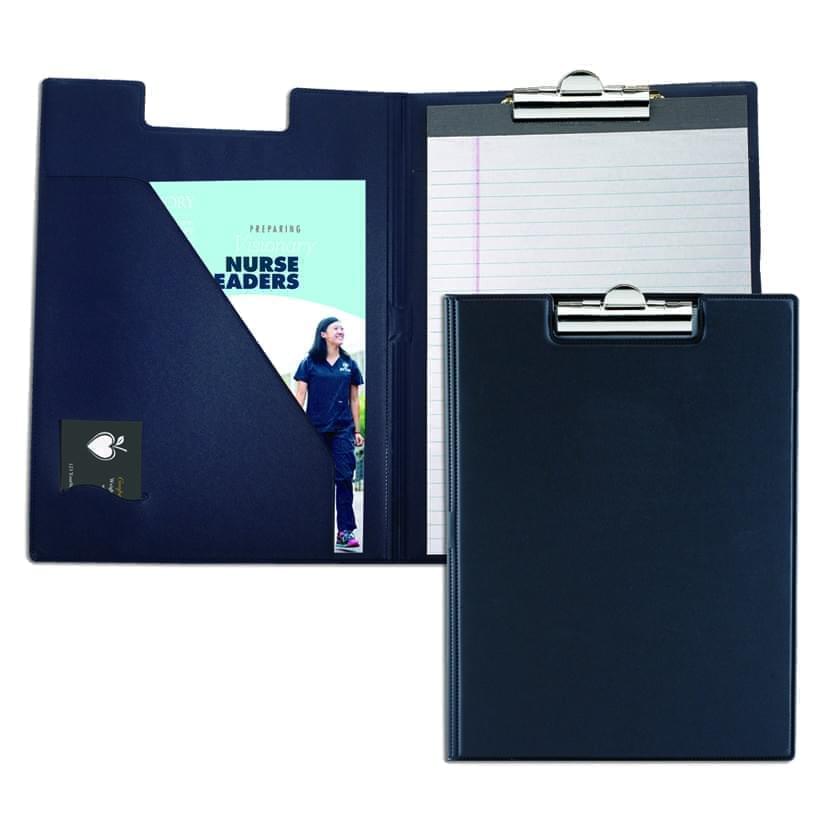

Clipboards

Clipboards

Union Made In USA

Union Made In USA